Kill Zone (2005, Dir. Wilson Yip)

Kill Zone (2005, Dir. Wilson Yip)

Welcome to the New Wave of Hong Kong police thrillers -- technically polished, solidly acted, visceral and brainy. So why does it feel like something's missing? Kill Zone offers a few clues to answer that one.

But first, the good stuff: Simon Yam is as reliable as ever as Chung, a guilt-ridden cop who adopts the daughter of a gangster who was killed before he could give evidence against crime kingpin Wang Po (Sammo Hung, decked out in a goatee and silk suits). Aiding Yam is a triumvirate of police buddies (Kai Chi Liu, Danny Summer, Ken Chang) who aren't above twisting the law to nail Wang, while Wang relies on a grinning assassin with a predilection for long knives (Jacky Wu). The wild card is Chan's imminent successor Inspector Ma (Donnie Yen), who has a reputation for hotheaded behavior and an unflinching moral code that doesn't take too kindly to Chan's efforts to frame Wang. Add in an over-the-top complication (Chan is suffering from a brain tumor that may kill him at any moment), and you have the recipe for hard-boiled mayhem, Hongkie style.

Kill Zone holds your attention from moment to moment, and of course the marquee martial arts stars (Yen, Wu and Hung) get to have their big throwdown at film's end, with even a nice karmic zinger thrown in. But does it all hold together? Not quite. Caught between the frazzled realism of the Infernal Affairs movies and the postmodern moves of a Johnnie To flick, director Wilson Yip can't quite commit in either direction. Everything with Yam and his cop buddies (all of whom are sketched out in deft if obvious strokes) sticks doggedly to the policier template, while Yen has little to do except glower between the scant action scenes. When the fights do come, the old-school kung-fu seems distinctly at odds with the story's downbeat grit. It's all filmed in slick style, and Yen's face-off with Wu in an alley is a pulse-quickener, but Kill Zone is neither flashy enough to appeal to the reptilian brain stem, nor deeply felt enough to register as a tragic drama.

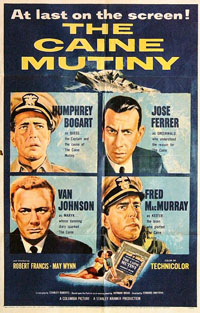

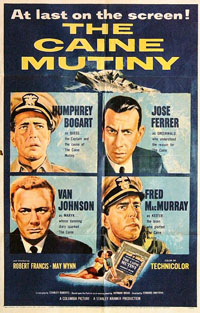

The Caine Mutiny (1954, Dir. Edward Dmytryk)

It's easy to forget that many of the classic Hollywood stars were most interesting when they went against type. Take Jimmy Stewart, who brilliantly inverted his everyman persona in his westerns with Anthony Mann and Hitchcock's films. Cary Grant often went from the height of urbanity to the depths of slapstick within the same film. And then there's Humphrey Bogart, who was never all that easy to pin down to begin with: always the hard-bitten cynic, his characters forever seemed an inch away from giving into darker impulses (we remember his bared teeth in The Maltese Falcon, his alcohol-fueled rage against Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca). One could say that The Caine Mutiny is the third of the "Bogart loses it" trilogy, and while it's not on the level of the other two (Treasure of the Sierra Madre and In a Lonely Place), it's a reminder of how good an actor he could be.

Based on the novel by Navy vet Herman Wouk, the novel is essentially a World War II remake of Mutiny on the Bounty -- that is, if you can picture the HMS Bounty as a garbage scow. Assigned to the minesweeper Caine to whip the crew into shape, Bogart's Commander Queeg quickly reveals himself to be a paranoid taskmaster on the verge of cracking up, as minor snafus (a sailor's shirt not tucked in) escalate into the accidental severing of a mine cable, an unordered retreat from a battle zone, rants about stolen strawberries, and finally faulty decisions during a typhoon that risks the lives on everyone on board. Wouk cannily splits his tale between two points of view: most of the action is seen through the eyes of Willie Keith (Robert Keith), a fresh-faced ensign from Princeton with illusions of naval grandeur, a girlfriend sick of waiting for him to pop the question, and a serious mother complex, while the latter stages of the film belongs to the "real author of the Caine Mutiny," Lieutenant Tom Keefer (Fred MacMurray), the ship's resident cynic and a frustrated writer who isn't afraid to throw the Freudian book at Queeg behind the man's back but is too yellow-bellied to go on the record about his boss's failings. (One wonders if Wouk divided his own persona between these two polar opposites.) Caught in the middle is the ship's super-competent, addled exec, Steve Maryk (Van Johnson in fine form), who bears the brunt of naval law when he decides to relieve Queeg.

The Caine Mutiny skirts the fine line between ambivalence and simplicity -- no doubt due to the ever-watchful eye of the Navy during production, the story is soft-pedaled a bit so that the sea services don't come off too badly (the film sets forth the quaint notion that a cowardly captain is an impossibility), and Keith's on-and-off-again romance with his girl (May Wynn) takes up far too much of the film's time. Still, there are surprising shades of gray (the Caine's lackadaisical crew aren't necessarily blameless in the affair), and director Edward Dmytryk does a fine job of pacing the narrative. He's aided by a stellar group of players, including scene-stealing Jose Ferrer in his final-act appearance as Maryk's legal counsel, Lee Marvin, and E.G. Marshall, among others (Francis is the weak link in the cast, but he is convincing enough as a by-the-book mama's boy). MacMurray in particular stands out: just glib and canny enough to foment trouble, like his Walter Neff from Double Indemnity, he nonetheless has a rueful side, all too aware of his cowardice: "I'm too smart to be brave," he quips.

As you would expect though, the film ultimately belongs to Bogart, teetering between naturalism and theatricality. Sure his habit of rolling steel balls in his hand is now near-laughable shorthand for "crazy," but every moment he is on screen he is the very definition of unpredictability, ready to erupt, implode, cajole, or plead; he supplies the film's buzz. While The Caine Mutiny may seem a bit stolid by today's filmmaking standards, one need only compare it to Tony Scott's Crimson Tide, wherein Denzel Washington and Gene Hackman take turns mutinying against each other to service another nuclear doomsday action scenario, to appreciate the former's devotion to character, and the outrage and sympathy it inspires for its tormented captain.

Labels: caine mutiny, donnie yen, fred macmurray, humphrey bogart, kill zone, sammo hung, simon yam, van johnson

Kill Zone (2005, Dir. Wilson Yip)

Kill Zone (2005, Dir. Wilson Yip)

Kill Zone (2005, Dir. Wilson Yip)

Kill Zone (2005, Dir. Wilson Yip)

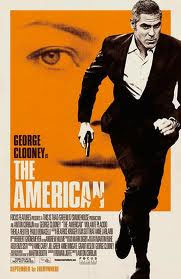

The American (2010, Dir. Anton Corbijn)

The American (2010, Dir. Anton Corbijn)

Still, this is Italy after all, the land of people and passions, and despite himself, the American is drawn into the lives of those around him: bemused interactions with the local priest who is out to save his soul (Paolo Bonicetti), faintly teasing repartee with his latest (and perhaps last) client Mathilde (Thekla Reuten), and most importantly, a half-guarded, half-passionate affair with a local prostitute named Clara (the aptly named Violante Placido). Juxtaposed against these detours into humanity is his latest job: the construction of a portable sniper's rifle for Mathilde. The scenes in which Clooney whittles, fiddles, deconstructs and reconstructs the rifle with a craftsman's ease are among the film's best. Despite his protests to the contrary (see the quote up top), the American is more than adept with machines -- he's quite the slick piece of machinery himself. (In a puckish bit of humor, renowned photographer Corbijn has Clooney pose as a photojournalist, rather than as the butterfly collector in Booth's novel).

Still, this is Italy after all, the land of people and passions, and despite himself, the American is drawn into the lives of those around him: bemused interactions with the local priest who is out to save his soul (Paolo Bonicetti), faintly teasing repartee with his latest (and perhaps last) client Mathilde (Thekla Reuten), and most importantly, a half-guarded, half-passionate affair with a local prostitute named Clara (the aptly named Violante Placido). Juxtaposed against these detours into humanity is his latest job: the construction of a portable sniper's rifle for Mathilde. The scenes in which Clooney whittles, fiddles, deconstructs and reconstructs the rifle with a craftsman's ease are among the film's best. Despite his protests to the contrary (see the quote up top), the American is more than adept with machines -- he's quite the slick piece of machinery himself. (In a puckish bit of humor, renowned photographer Corbijn has Clooney pose as a photojournalist, rather than as the butterfly collector in Booth's novel). If you think the above suggests a simmering psychological study, you would be half-correct. In a welcome change from the excesses of most modern thrillers, Corbijn keeps things cool and elicits solid performances from his actors, his sinewy camerawork resisting the temptation to show off (save for a couple of gaudily lit nighttime shots that look like outtakes from U2's latest album art). In the end, though, the story is too slight to convince as a character study, and overdone symbolism (tattoed and real butterflies make constant appearances) and clunky dialogue take hold, with the affable Bonicelli saddled with lines that belong in a late-period Goddard film: "You are American. You think you can escape history. You live only for the present." Clooney's dogged (and hangdog) performance is credible, and it's a pleasing thrill when the American begins to suspect that he may be constructing the instrument of his own doom, but Corbijn sidesteps the existential implications -- and thus the thrust of Booth's novel -- in the latter half of the movie to focus on the doomed love between Clooney and Placido. Ah yes, the romantic fatalism of noir, what could be more American?

If you think the above suggests a simmering psychological study, you would be half-correct. In a welcome change from the excesses of most modern thrillers, Corbijn keeps things cool and elicits solid performances from his actors, his sinewy camerawork resisting the temptation to show off (save for a couple of gaudily lit nighttime shots that look like outtakes from U2's latest album art). In the end, though, the story is too slight to convince as a character study, and overdone symbolism (tattoed and real butterflies make constant appearances) and clunky dialogue take hold, with the affable Bonicelli saddled with lines that belong in a late-period Goddard film: "You are American. You think you can escape history. You live only for the present." Clooney's dogged (and hangdog) performance is credible, and it's a pleasing thrill when the American begins to suspect that he may be constructing the instrument of his own doom, but Corbijn sidesteps the existential implications -- and thus the thrust of Booth's novel -- in the latter half of the movie to focus on the doomed love between Clooney and Placido. Ah yes, the romantic fatalism of noir, what could be more American?