Bless the Castro Theatre -- for old codgers like me (read: people born before 1980), the theater is a treaure trove of golden oldies, forgotten classics, and themed programming. Sure you can probably see many of the films that play there on TV or in pristine DVD prints, but there's something about seeing something on that old-fashioned screen, the ornate palatial walls reminding us that the movie-going experience was like attending mass. It also helps when you're attending a James Bond film festival.

I make no secret about my love of all things Bond, and a mini-festival afforded me the opportunity to catch four films, classics all. In viewing them (in some cases, seeing them on the big screen for the first time), I'm reminded of how elastic Bond is as a cinematic and cultural phenomenon, and I'm also intrigued by how established notions about each of the actors who have played 007 and their movies don't necessarily relate to the actual films themselves. As I took a trip down memory lane, I also found that old critical faculty kicking in, and discovered new things to savor and ruminate over.

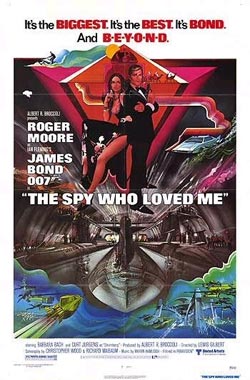

The Spy Who Loved Me (1977, Dir. Lewis Gilbert)When you're going downhill on skis at forty miles an hour and someone's trying to put a bullet in your back, you don't always have time to remember a face ... In our business, Anya, people get killed. We both know that. So did he. The answer to the question is yes. I did kill him. -- James Bond, The Spy Who Loved Me

Anticipation for this movie was high, as the special guest of the festival was Richard Kiel, who played the infamous henchman "Jaws" in this film. Now sadly confined to a wheelchair, he could nevertheless make a crack about his condition: "Sorry to be here like this, but I fell out of an airplane without a parachute." In the brief Q&A preceding the film, he noted that he attempted to inject a bit of personality into his heavy (impatience and frustration at Bond always escaping his clutches, little grace notes like brushing off his suit after getting ejected from a moving train). He also mentioned that two different endings were filmed for the character -- one in which he was eaten by a shark, another where he

eats the shark and swims away to safety, ready to battle another day (another day coming in the inferior follow-up to this film,

Moonraker (1979) -- talk about jumping the shark). When a preview audience went berserk at seeing Jaws survive, his immediate future (and enduring legacy) was secured.

Primed after that introduction, watching

The Spy Who Loved Me was a joyous experience. The movie holds a special place in my heart since it was the first Bond film I saw in the cinema, and time has been kind to it. Still as slick, gargantuan, and visionary (yes, visionary) as when it came out, it still stands as a high-water mark in the series, and an apotheosis: no Bond film since has matched its scale and easy jet-setter elegance (although some have tried).

The Spy Who Loved Me marked a pivotal moment in the Bond saga -- with co-producer Harry Saltzman leaving the fold after nine movies, godfather producer Albert "Cubby" Broccoli had to go it alone, and he spared no expense, even though the previous entry,

The Man with the Golden Gun, had underperformed at the box office. Broccoli responded to the challenge of making Bond relevant again by fashioning the first self-aware Bond epic -- while previous films acknowledged Bond's place in the popular culture with a knowing wink, this was the first Bond movie to borrow wholesale from previous entries, a "greatest hits" cornucopia if you will (the basic plot is lifted pretty much intact from

You Only Live Twice). That the film succeeds as well as it does is a testament to the energy and craft of the production team (and lest you think a "greatest hits" package should be an easy thing to enjoy, I refer you to

Die Another Day).

Oh, it's indulgent all right, in the way most Bond movies are indulgent. We globe-hop from Austria to Egypt to Sardinia

because we can and not because of any rigorous plot logic, and the dastardly plan by villain Karl Stromberg (a phlegmatic Kurt Jurgens) to set off World War III in order to jump-start a new kingdom beneath the sea is the sort of rule-the-world daffiness the series can't get away with now in the wake of Austin Powers. And that's not even mentioning the various Bond mots that induce simultaneous laughs and winces: "When one is in Egypt, one should delve deeply into its treasures"; "Let me try and enlarge your vocabulary"; "Such a handsome craft -- such lovely lines." Watching the movie is a warm reminder of a more innocent time, in which such shenanigans could be looked upon as high style.

|

The reason the film still works is because it actually attains the high style it aspires to. The crackerjack opening sequence, replete with the famous "ski off a cliff and open a Union Jack parachute" showstopper continues to thrill, especially now that we know such a feat would be produced today with CGI and not agonized over with a real stuntman. The travelogue views of Egypt and the Italian coast are captured with aplomb by the great Jean Renoir (descendant of Claude Renoir), and production designer Ken Adam was never more expressive with his stainless steel sets, juxtaposing mammoth lairs (the interior of the tanker that swallows up hapless Allied submarines ranks as one of the best villain bases of the series) with sexy curvilinear hideouts (dig the escape sub that looks like the olive in a martini glass). And then there's the theme song, "Nobody Does It Better," by Carly Simon; sweetly soaring and romantic, it has the assurance of a hit Broadway tune, and it pins the mood of the movie exactly -- you're going to get a little bit of danger, a little bit of romance,a little bit of comedy, and everyone's going to have fun.

|

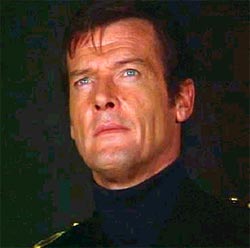

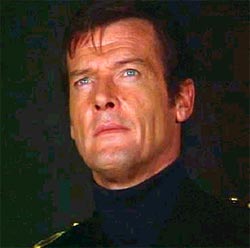

Roger Moore gets a bum rap from many a 007 aficionado, but not from me -- sure he's a far cry from the Ian Fleming character, but in his own distinctive way, he has left his stamp on the series, for no one can go into a Bond movie anymore without expecting smirking wit and debonair

savoir faire (just see how people reacted when the anything-but-suave Daniel Craig was announced for the role). Conventional wisdom says that Roger was a fatuous jokester who reduced the role to a parody, but in

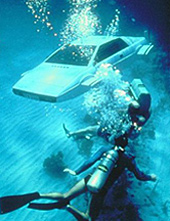

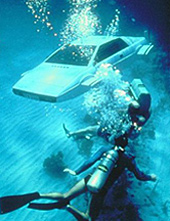

The Spy Who Loved Me he pulls off a difficult balancing act. For every raised eyebrow and self-satisfied pun he tosses off, there is a counterbalancing moment that actually suggests three dimensions. Take the unfussy, perfectly judged scene in which his counterpart, Russian agent Anya Amasova (Barbara Bach is no actress, but her va-va-voom factor is up there with the best of the Bond girls) starts reciting the facts of his background. The moment she mentions his late wife, Bond's face clouds over and he cuts her off brusquely -- certainly not the "we're only in it for the fun" Roger Moore stereotype. Or take a later confrontation with Anya in which Bond admits that he was probably the man who killed her lover in the pre-credits ski chase: no tricks, no camera cuts to hide any actorly weaknesses here, only Moore playing the scene completely straight, and achieving a dramatic effect that someone like Pierce Brosnan could only dream of. Or savor his execution of Stromberg at the film's climax, as he coldly fires two superfluous bullets into the fallen man -- James Bond the assassin, through and through. His unruffled likeability his secret weapon, Moore is never more interesting than when he slips into seriousness, the transition as smooth as a shift of gears in his Lotus Esprit sports car.

|

It's a good thing he's in top form here, because the film does get a bit noisy and overproduced by the climax (an affliction common to the Bond films). Still, a sense of grand fun permeates the proceedings, and the gadgets this time out have a kid-in-the-toy-store glee to them, especially that Lotus Esprit, which turns into a sub bristling with rockets, smokescreens, and mines. Crucially,

The Spy Who Loved Me never forgets that the best Bond movies have a core seriousness even at their most outlandish. Death is always waiting around the corner in the form of Kiel's Jaws, who features in some grisly executions (he likes sinking his steel teeth into his victims' necks Dracula-style). While Moore's face-offs with Kiel don't have the rough-and-tumble choreography we associate with today's buffed-up action heroes, they do have more wit to them (be careful around lamps or you might get short-circuited), and Moore's looks of alarm humanize his Bond -- sure he's smooth as silk, but he gets just as worried as the rest of us would be when confronted by a seven-foot-tall assassin with steel dentures. Likewise, the film's climax aboard the enemy tanker is a riot of choreogaphed mayhem, but it's stage-managed with brisk clarity by Lewis Gilbert, who has been better than any other Bond director at capturing the spectacle of armies duking it out within a confined space.

|

It all ends -- as Bond films usually do -- with the comforting sight of Bond bedded down with his latest conquest, surprised by his higher-ups, getting off a final zinger ("Just keeping the British end up, sir"), the theme song ushering us out on a high. "Nobody does it better," Carly Simon croons, and the film lives up to that boast. Formulaic as it most certainly is,

The Spy Who Loved Me luxuriates in the Bond-ness of it all, content to wallow in the standard tropes and present it all with a cheeky smile and pop-art polish. We will probably never see its like again.