Ho Lin's official blog site -- home to Ho's commentary, film and book reviews, and meanderings about life.

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

Monday, May 26, 2008

Friday, May 23, 2008

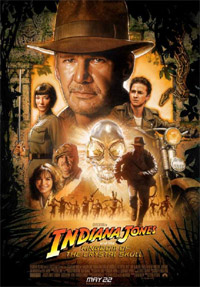

Raiders of the Lost Youth: "Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull"

|

It's not the years honey, it's the mileage.

So said Indiana Jones (Harrison Ford) back in 1981, in Raiders of the Lost Ark, and 27 years on, those words take on an additional poignance. Now it's about the years and the mileage, as the 65-year old Ford and weathered filmmakers Steven Spielberg and George Lucas release the fourth chapter of the Jones saga. As Spielberg has said, there was never a pressing need to make this film -- the third film, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), concluded with Indy and his tetchy father, Henry Jones Sr. (Sean Connery) literally riding into the sunset, and in the protracted hiatus since then, rumors and ideas for a new adventure floated about much like the crazed spirits that were released from the Ark of the Convenant in Raiders. No, claimed Spielberg, this film wasn't necessary, but it would be a valentine to the fans, a salute to their devotion to their pulp hero over the years.

Raiders still towers over the genre as its own unique creation -- unashamedly inspired by the pulp serials of Lucas and Spielberg's youth, it upped the ante with A-class production values, a knowing sense of humor, and action sequences that were fleet-footed and bone-jarring. Raiders' lesser sequels Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) and the Last Crusade tended to lean towards cartoonish bombast, but the die had been cast: these films set the template for action extravaganzas of the '80s and '90s, and their influence can be seen everywhere, from the increased action quota in the recent Bond films to the Da Vinci Code and the tongue-in-cheek "hunting for buried artifact" hijinks of Sahara and National Treasure.

|

|

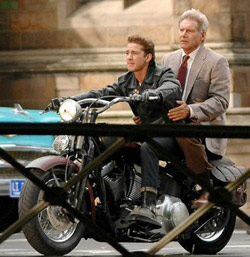

For a while Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is genial entertainment, preferring to lay back and lay on the exposition while pep is added with a few nifty action sequences. Certainly it approximates the look and feel of your standard lavish Indy adventure, as cinematographer Janusz Kaminski deliberately echoes the great Douglas Slocombe's rich palette from the '80s films. The movie's major setpiece, a motorcade chase in the jungle in which the antagonists find themselves playing musical jeeps, has a sprightly momentum when it's not cutting away to the sight of Mutt making like Tarzan with a multitude of CGI monkeys.

|

|

|

Sunday, May 18, 2008

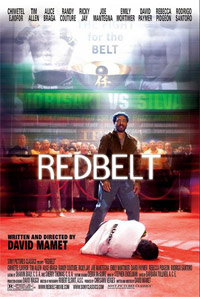

Dodge and Parry: "Redbelt"

|

Let's go to court ... let's go to Brazil ... Insist on the move, insist on the move ... Improve the position, improve the position ... Breathe. Breathe. Look for a way out. There's always a way out.

Couched in the vocabulary of mixed martial arts, the rhythms of the above quotation are rat-tat-tat, as you would expect in any action film concerning humans pummeling other humans, and yet in their insistence, their obsessive repetition, they could only have come from one man: David Mamet, playwright, film director, and black-belt jiu-jitsu artist. It seems almost shocking that Mamet has never tackled a film in the martial arts arena before -- the idea of a ritualized confrontation between two men in a ring is a perfect counterpoint to Mamet's verbal jousts, which are just as bruising as any physical combat.

But there's more to Mamet's work than conversational pugilism -- he habitually undercuts his foul, fast-talking characters by plopping them in a funhouse of cons, feints, and trickery. In House of Games, The Spanish Prisoner, Spartan, and others, the verbal volleyball serves as the dense surface beneath which the machinations of plot, fate, and a cruel world threaten to overwhelm his heroes.

|

|

Mamet sprinkles plenty of red herrings and suspicious hints in the narrative -- there's the cocky magician (Randy Couture), a Brazilian fight promoter (Rodrigo Santoro) who happens to be Sondra's brother, the faxing of a document of fighting rules that may or may not constitute property theft, a gold watch that might be stolen goods, and walk-on parts by Mamet standbys (David Paymer, Rebecca Pidgeon, Jay, Mantegna) as affable managers, cultured wives, sympathetic loan sharks. Yep, it's as fishy as a salmon processing plant, and it's saying something that Laura the lawyer turns out to be the most honest of the bunch.

|

|

Saturday, May 10, 2008

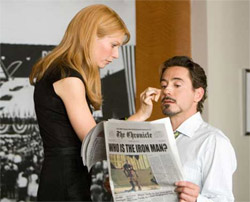

Light Metal: "Iron Man"

|

Jim Rhodes: That's the coolest thing I've ever seen.

Tony Stark: Not bad, huh?

Among the ever-growing pantheon of movie superheroes based on Marvel comics, Tony Stark (aka Iron Man) is unique -- rich as Bruce Wayne but ten times the wiseass, brilliant as Reed Richards but way hipper, as human as Peter Parker but with more grown-up concerns -- a drinking problem and assorted pieces of shrapnel lying inches away from his heart, for example. It's only fitting then that the first in what will surely be many films featuring the character is the first superhero film for grown-ups that we've seen in a while.

Oh sure, we've seen plenty of "mature" superhero movies -- Batman Begins and The Punisher, just to name two. But subtract the grim trappings of those films and you're essentially left with adolescent wish fantasies. In Batman's sex-less universe, the prospect of a mature relationship with a woman would seem just as outlandish as, well, dressing up as a bat to fight crime. Likewise, the Punisher is too busy cracking skulls to even contemplate a romantic entanglement (and if Thomas Jane couldn't get excited at the prospect of Rebecca Romjin in the film version, then there's simply no hope).

|

|

|

|

|

Tuesday, May 06, 2008

SFIFF '08: "Not By Chance"

|

"We are all particles. We move. That's what we do. We attract and repel."

-- Enio, Not By Chance

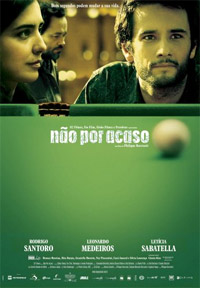

What does it say about world cinema when the latest export from Brazil (São Paulo, to be exact) could easily be mistaken for a Wong Kar-Wai movie? Perhaps everything, perhaps nothing. When a film like Mongol borrows its aesthetic and plotting from Gladiator, and a Thai film like The Unseeable (which I caught at the recent Asian-American film festival) is more M. Night Shyamalan than Bangkok Dangerous (getting remade as a Nic Cage potboiler, by the way), it's clear that filmmaking's cultural and ethnic boundaries are breaking down, or going very gray.

As a believer in Mikhail Bakhtin's theories on multivocality, though, I'm all for these collisions of time and place and influence. If other arts have become a goulash of influences and stolen motifs, why not do the DJ mash and revel in the odd combinations that result when you throw everything in?

Which is not to say that Not By Chance, the first feature-length film by shorts director Philippe Barcinski, is a confused mess. In its precise intersection of individuals and tragic events, it's Crash minus the hysterics. In its laid-back romanticism, it's an antidote to recent Brazilian films like City of God which launched Mean Streets-style filmmaking into the stratosphere with its presentation of a lawless, bombed-out São Paulo. Not By Chance is São Paulo rehabilitated as urban wonderland, sometimes dangerous, oftentimes lonely, but with a hint of reconciliaton at the end of the road.

|

|

Not By Chance is a slick affair -– the opening helicopter shots of the city, with the film's titles floating by on the sides of skyscrapers, are a direct lift from David Fincher's Panic Room, and suggests that we might be in for a heavy-handed thriller or drama. We're spared from such a fate, although Barcinski sometimes gets a little cute. At one point, a character's fate is decided when she decides to run out of the house instead of tarry for two seconds, and like a photographic afterimage, we see what would have happened if she lingered for those extra two seconds -- it's an episode of Hesitate, Lola, Hesitate. All the usual elements of urban fantasia are in place: snapshots of lovers that gain totemic significance, a burnished afternoon spent at the local park, the idea that a career-minded businesswoman would fall for a young ne-er-do-well in the span of a single day. But above all, Barcinski is a graceful director, his short-film training making him adept at indicating a cliché and moving on before we're overcome by the hoariness of it. Like Wong Kar-Wai, he is a breezy humanist: none of these characters are necessarily complex, and yet he has sympathy for them as they tend to life on their own obsessive terms. While Wong's plots are overwhelmed by saturated cinematography and his characters' oblique ruminations, Barcinski is more of a straight shooter. He shoots in simple, unadorned yet attractive style; best are the passages in which characters are allowed to walk in and out of focus, their intimate moments crystallized seconds at a time.

|

Thursday, May 01, 2008

SFIFF '08: "Mongol"

|

We've come a long way, baby. Or have we? In 1956 Howard Hughes took a stab at the Genghis Khan myth when he produced The Great Conquerer, which is generally acknowledged as the worst film John Wayne ever starred in. Filmed in Utah (where, as urban legend has it, radioactive soil caused the eventual deaths of Wayne and dozens of other crewmembers to cancer), burdened with the, ahem, unusual sight of John Wayne playing the great Mongol in a Fu Manchu mustache, The Great Conquerer belongs squarely in the "so bad it's hilarious" category of shlock moviemaking, and we haven't even mentioned Susan Hayward as a spirited Mongol highlander.

Flash forward half a century later, and in our search for the latest exotic, far-flung, mystical land to canonize, the wheel has spun around to land on Mongolia once again. So instead of a big-budget Hollywood production starring a Caucasian cowboy as the Khanmeister, we get a joint Russian-Khazakstan-Mongolia production helmed by a German, with a Japanese man (Asano Tadanobu) as the Khanmeister. It's progress of a sort, I guess.

|

|

There's plenty of combat, of course, and the battle scenes, replete with CGI weather effects and arterial blood sprays, should satisfy most slaughterhounds. Better still is Sun Honglei as Jamukha, Temudgin's blood brother and eventual greatest rival for control of the burgeoning Mongolian empire. Of all the actors, Sun seems to be the only one who is aware that this is all a bunch of hooey; armed with a proto-punk buzzcut that is sharper than any blade wielded in the film, he chews the scenery to pieces, his wry little twists of the head and musical mutterings serving as punchlines. But best of all is an almost anecdotal passage in which a Chinese monk attempts to help the imprisoned Temudgin by transporting a bone necklace charm to Borte. As the monk wordlessly crosses mountains and deserts on foot, dogged in his determination even as his body slowly fails, one finally catches the whiff of genuine mythmaking.

|

Mongol does exactly what it intends to do; it serves as the launching pad for a sequel or two (the end of the film practically begs for the subtitle "To be continued…"), and does it with what passes for epic style these days – a few monumental vistas, a few faces covered with grit, a few shouts of anger and slashes of sword, appropriate swells of music on the soundtrack, and a storyline that would snuggle comfortably inside a comic (Conan the Barbarian, anyone?). But whatever your reaction to the film, you can still marvel at the magnificent scenery and dream your own dream of a epic that would be more intimate and substantial than what we see on screen. We've come a long way, baby.