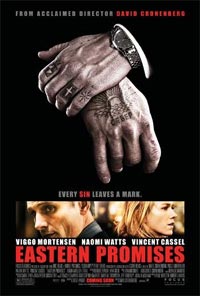

Eastern Promises (2007, Dir. David Cronenberg)Sometimes, if things are closed, you just open them up.-- Nikolai Luzhin, Eastern Promises

"Cold-blooded" might be an adjective used to describe the work of David Cronenberg, but I prefer the term "exploratory," as in exploratory surgery. He takes pleasure in dissection: carving open mundane surfaces to analyze the rot underneath, peeking beneath the veil to exult in savagery. At his strongest when he applies this approach to pulp concepts -- the gonzo snuff TV of

Videodrome, the human-body-as-horror hijinks of

The Fly -- he is like the disinterested coroner who nevertheless breaks into little-boy smiles now and then, as if he's remembering the time he pulled wings off insects.

Cronenberg's recent

A History of Violence has been his most critically lauded film, but it also marked an impasse -- on the one hand, it was his most mainstream project to date (based on a graphic novel, no less), and yet his deliberately styled tableaus and off-kilter framing were as prevalent as ever. Here his technique butted heads against a pulp story that resisted all attempts at aesthetic uplift, leaving us with a few nifty scenes of slaughter, punctuated by acting that ranged from stiffly naturalistic (Viggo Mortenson) to hambone juicy (Ed Harris and William Hurt). Formally intriguing and ice-cold,

History's ultimate point seemed to have something to do with the violence in men's souls, or something portentous like that, but what it really should have been was a down-and-dirty gangster yarn. There was plenty of viscera on the screen; what was lacking was the sweat.

Eastern Promises seems like a retread of that vision in its initial scenes: on a rainy London night, a Russian mobster stops in for a cut at the local barbershop, only to have his throat slit in excruciating detail, and a young pregnant prostitute stumbles into a drug store, blood pouring from her innards (Grand Guignol, here we come). Yet Cronenberg has something different in mind this time; after this opening salvo, he settles into a style that is more measured, more patient with setting and characters. The prostitute dies giving birth, leaving the baby and her secret journal in the care of the midwife Anna (Naomi Watts). Unable to decipher the journal, Anna ends up consulting her belligerent, old-school Russian uncle (a delightfully tetchy Jerzy Skolimowski), and when she is essentially told to let the dead lie, Anna, seized with a sense of responsibility for the infant, and burdened by the recent death of her own baby, follows a lead to the restaurant of Semyon (Armin Mueller-Stahl). Big mistake -- the affable Semyon is a major player in the Russian mob, and the prostitute belonged to his skittish son Kirill (Vincent Cassel). When Anna persists in her line of inquiry, she runs afoul of father and son, as well as their trusted chauffeur and "undertaker" Nikolai (Mortenson).

|

The screenplay is by Steven Knight, who mined similar territory in

Dirty Pretty Things -- the innocent woman thrust into a scuzzy London underworld in which her ignorance serves as a shield, at least for a while. As we tour the Russian mobster milieu, we note points of interest: the perfect spot to dump a corpse in the Thames; the meaning of criminal tattoos and their placement on the body; the value of classic Russian motorbikes and how to fix them; a scene in which a forlorn prostitute moans a folk song from the old country juxtaposed against a passage in which Semyon regales a customer with a happy tune of his own. Aided by some solid acting (Mueller-Stahl radiates menace without racing his voice above a conversational hiss, while Cassel goes into full bonkers mode), Cronenberg lets the film breathe as the complications mount. Clearly this is his most conventional work yet, but his looser, more off-the-cuff approach is a good fit for the material. Make no mistake, it gets downright ugly at times, especially when the neurotic Kirill orders Nikolai to prove his loyalty by fucking an underage girl, and as the mobsters tighten their grip on Anna and her family, we steel ourselves for the inevitable bloodbath.

|

It happens, but not in the way we expect. In a subtle but definite shift of focus, Anna's role is marginalized and we find our sympathies aligned with Nikolai, the low-level gangster angling for respect, caught with what seems to be a burgeoning conscience as he finds himself attracted to the stalwart Anna. As Anna, Watts can't help but be radiant, but hers is too open and sincere a character; Cronenberg instinctively gravitates towards Mortenson's Nikolai, the diffident mobster with the ready smile and the masklike countenance, someone who obviously has secrets. The same qualities that rendered Mortenson unconvincing as a gangster gone "straight" in

History of Violence -- the calculation, the sense of detachment, the smidgen of gallows humor -- serve him brilliantly here. Though his performance has plenty of wry humor to it, as when he extinguishes a cigarette on his tongue with perfect comic timing, the tragedy of his character mirrors the mood of the film. Shot in muted grays and browns,

Eastern Promises is a mournful picture, and Mortenson is the most mournful one of all; privy to the bad things that men do and partaking of it himself, he is constricted by caution, resigned to doing wrong and obeying the vicious thugs who are his stepping stone to better things. Or at least it seems that way -- to give away the ending would be wrong, but suffice to say that the slow-cooking tension Cronenberg builds throughout comes to a full boil when vengeful Chechnyan assassins track down Nikolai at a bath house, setting off a struggle in which a very naked Mortenson must fend off two attackers with nothing but animal fury on his side. It's a brutal smackdown that is virtuosic in its choreography and sound design, as we feel each slash of the knife as it slams into Nikolai's skin, and clench our teeth as he stabs a would-be assassin in the eye.

|

It would be difficult to top a sequence like that, and Cronenberg doesn't even try; in its last twenty minutes the film decelerates like a wind-up toy running out of steam. A character revelation arrives from left field, and a climax involving Kirill, Nikolai, Anna, the baby, and the Thames River ends it all on a wistful, bittersweet note. As with just about all of Cronenberg's movies,

Eastern Promises concludes in a Pyrrhic victory: the forces of order are restored, and the various promises that have been made throughout the film are all kept in a fashion, but at what cost? What is most striking about the denouement is the sense that the story is still moving, with plot threads begging to be picked up, characters missing in action or on the make. Still, the last image of Mortenson alone at a dinner table, all dressed up and no place to go, seems as final as you can get, and its sadness signals something new in Cronenberg; while it may not cohere as well as some of his other works,

Eastern Promises suggests that empathy and soul may not be as far out of his grasp as we might have thought.