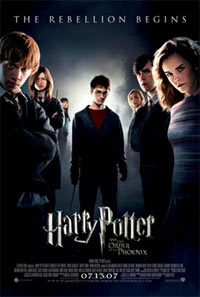

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007, Dir. David Yates)I just feel so angry, all the time. And what if after everything I've been through, something's gone wrong inside me. What if I'm becoming bad?-- Harry Potter

Harry Potter is an unavoidable fact of our lives, but I always enjoy talking with true Potter-heads, those who have absorbed every arcane bit of knowledge from J.K. Rowling's series, much like Harry pores over dusty old tomes at Hogwarts on a wonderfully dreary Sunday afternoon. As someone with my own obsessions (James Bond, anime, NFL 2k5), I always recognize the wavelength of a True Believer: gaga over the virtues of the thing they love, forgiving of its faults, content to enjoy and explain to others why they enjoy. I am assured by my Potter-loving friends that the Harry Potter movies are better understood and savored when one understands the motivations behind a fleeting supporting character, or the backstory that explains how Harry's prodigious father wasn't such a nice guy after all. Doting and amiable, Potter fans tell me that book five,

The Order of the Phoenix, is a pivotal moment in the saga, in that Harry finally decides to

do something and rebels against the dark fate that has been ordained for him -- to which I can only reply,

Well good, I'm glad he's doing it ... and it only took FIVE BOOKS to reach this point ...I must resign myself to the realization that I'm probably out of step with this Potter phenomenon anyway. My Potter friends seem united in their conviction that the fourth entry of the movie series,

The Goblet of Fire, was easily the worst of the lot, while in my mind it was the best -- for all its sloppiness of construction, there was a kernel of real teen angst at the heart of it, and a restlessness which hinted at greater travails to come. Those travails come hot and heavy in the film version of

The Order of the Phoenix, which just as well might have been titled

Harry Gets Pissed, and for once there's no pussyfooting around when it comes to the story. Within the first fifteen minutes, Harry comes under attack by Dementors (and in case the name wasn't enough of a giveaway, we're informed that Dementors are very bad), takes a broomstick flight down the Thames, meets up with a rebel faction of sorcerers, and is threatened with expulsion from Hogwarts. Clocking in at under two and a half hours, the rest of the film is similarly jam-packed, the Harry Potter experience distilled and intensified -- more ghoulish apparitions, more hushed whisperings of conspiracy and murky motivations within sealed-off rooms, and a wizard-on-wizard smackdown that will send the kiddies home screeching with joy.

All flipness aside,

The Order of the Phoenix has much to recommend it. As ever, the production design and special effects are impeccable, detailed enough to exude wonder and just fake enough to avoid being labored. The juxtaposition of the magic world and the real world generates some lyrical moments, as when Harry and his sorcerer pals take to the night skies of London on their broomsticks and peel past the houses of Parliament -- at moments like these, the Potter series stakes its claim to being the offspring of other English fantasies such as

Peter Pan and

Mary Poppins, where the commonplace and the fantastic collide. As with other entries in the Potter series, a good part of the fun is spotting the latest esteemed English actor slumming it in a walk-on guest role (hint -- two of Kenneth Branagh's squeezes show up). The standout this time is Imelda Staunton, who is alarmingly giddy as the matronly Dolores Umbridge, a guest lecturer under orders by the Ministry of Magic (bureaucratic and short-sighted, natch) to put free-thinking Hogwarts Headmaster Dumbledore in his place, and ensure that any signs of liberal thinking within the academy are swiftly quashed. Deliciously officious, Staunton reminds us why we have a soft spot for stories about school academies -- it's the never-ending struggle between childlike mischief and po-faced adult strictures.

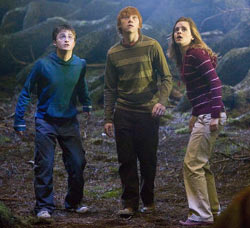

Unfortunately, Umbridge's appearance just means more misery for poor Harry (Daniel Radcliffe), who is still smarting from his near-fatal encounter with the dread wizard Voldemort (Ralph Fiennes) at the climax of his previous adventure. Naturally, no one at the Ministry or the Academy, save the ever-trusty Ron (Rupert Grint) and Hermione (Emma Watson), actually believe that Harry actually encountered his archenemy, and thus, he must be muzzled -- any resemblance to any current real-world government is purely coincidental...

If

Goblet of Fire really belonged to Emma Watson, whose impatient outbursts barely concealed the yearning, anxious young woman underneath, then

Order of the Phoenix belongs to Radcliffe's Harry. [An aside: it's sad to note that Watson's acting seems to have worsened between films.] Snapping at his bullying school tormenters, going head-to-head with the venal Umbridge, and eventually forming his own army of schoolmates as they ready for the coming war with Voldemort, this is a Harry who is prickly and proactive, or at least as much as he's allowed to be in a family film (his outbursts are noted, but their consequences are never lingered over). When the action is focused on him and the school year at Hogwarts,

Order of the Phoenix whizzes along at an agreeable rhythm, with plenty of fun grace notes: the unusual spectacle of batty Gary Oldman playing a wise, paternal figure; macabre methods for dealing with recalcitrant students (how about getting your hand carved up?); a CGI giant that is simultaneously comical and ominous; and a school examination that gives way to a riotous explosion of fireworks and teen rebellion.

The Potter universe seems to function best when it comes to these episodic little flourishes; it falters when it comes to an actual throughline for the plot, which this time hinges on an important piece of information about Harry's future which is (gasp!) hidden in a secret location. All but ignored for most of the film, the quest for this information leads to yet another showdown between wizard and wizard, the loss of another friend, another glimpse of Harry's destiny, and then ... whoops, school year is over, so until next time ...

Depressingly, much of what actually happens in

Order of the Phoenix reeks of

deja vu -- once again Harry is disbelieved, once again there is a showdown with Voldemort in which Harry is bailed out by an adult, once again the story ends on an inconclusive note. Scripted like a Saturday morning cartoon serial writ large, the Potter series holds true to the idea of leaving the audience wanting more, while forgetting to throw that same audience a juicy narrative bone. Director David Yates knows how to keep things moving, and it's clear he has an affection for this universe, but the dollops of personality that Alfonso Cuaron and Mike Newell heaped on the

The Prisoner of Azkaban and

The Goblet of Fire are in scant evidence here. There are a few gestures towards emotional resonance, including Harry's first kiss with Katie Leung's forgettable Cho Yang (a moment that is as chaste as an after-school special but still generated plenty of oohs and ahs from the young audience I saw the film with), and the implication that Harry is poised on the knife-edge between good and bad, but there's nothing about Radcliffe as an actor that suggests an inner Darth Vader raring to break out.

Perhaps this review comes off as sour grapes -- all Potter fans who line up to see

The Order of the Phoenix will most likely go home satisfied, and isn't that what really counts? It all comes back to J.K. Rowling, and the books that started the craze in the first place. It's no wonder that Harry Potter has captured the hearts of millions; his world is just idiosyncratic yet comfortable enough to nestle into our imaginations. Yet that same fussiness that Rowling has applied to her characters and settings threatens to throttle the life out of her plots, which grow unwieldy with secrets, unexplained prophecies and none-too-thrilling twists and turns. Yates does what he can with

The Order of the Phoenix, and he deserves some sort of medal for compressing Rowling's rogue narrative into something relatively streamlined. With any luck, he'll keep the pacing up with the next installment of the series, which he is slated to direct, and find a little bit more time for some authentic angst.