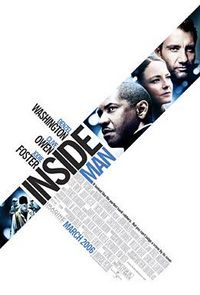

Confidence Scam: Spike Lee's "Inside Man"

|

"As for why? Because I can."

Slowly, almost imperceptibly, Spike Lee has evolved. The man who admonished us to Do the Right Thing, the director who brought the same "these are my peeps so I'm perfect for this job" brio to Malcolm X that Spielberg brought to Schindler's List, the first mainstream NYC filmmaker to tackle what it actually means to live in post-9/11 New York (25th Hour), has expanded his world view past polemics to ... a heist caper?

If you were in theaters during the 2005 holidays, you were likely exposed to two surprising trailers -- one for Woody Allen's Match Point (which played like Masterpiece Theater meets Fatal Attraction), and one for Spike's Inside Man. The latter, with its swooshing pans of gleaming bank vaults and automatic weaponry, its verbal fencing between Denzel Washington and Jodie Foster, its intimations of showdowns and thriller mechanics, "big budget" seemingly imprinted on every frame -- seemed a flat-out unlikely project for Lee. "Sellout," in short. And even though we are informed by the main titles that this is indeed a "Spike Lee joint," there is more than a bit of self-parody in the fact that Lee's name in the credits is perched above two street signs, the intersection of Wall Street and Broadway. Yes, the man from Bed-Stuy has moved up to the Big Time.

The truth turns out to be trickier than that, thankfully. Inside Man is a fascinating melange of competing impulses. On the one hand, you have the frame of a nothing-is-what-it-seems thriller written by Russell Gewirtz, replete with supervillains who have every possible angle covered, sweaty policemen racing against time to prevent the perfect robbery from ... asleep yet? On the other hand, you have Lee presenting the whole affair within ironic quotations, taking pleasure in presenting New Yawk and New Yawkers in all their snarky, absurd, humane glory, slipping in cultural observations like dabs splashed on the canvas.

|

Likewise, the story seems locked in its own head, resorting to stock cliches in depicting its true villains -- those rich white millionaires behind the scenes with secrets to hide. It's more than a bit ridiculous, since it asks us to buy a hale-looking Christopher Plummer as a slick upper-crust operator (no problem there) who would have to be more than 85 years old, not to mention the possessor of incriminating documents that any man in his position would have burnt eons ago. And not only that, we have Jodie Foster as his representative, "Ms. White" (subtle). Her profession is never made clear, but she is apparently a "facilitator" with enough clout to push the mayor around (Mr. Koch and Mr. Bloomberg, beware Peter Kybart's broad interpretation) and broker superdeals with Owen's super-criminal. A plot device and nothing more, Foster struts around in heels and aggressive suits, all but smirking at her own duplicity. Whenever the film zeroes in on her or Plummer and their Ivy League skullduggery (Shakespeare and Baron Rothschild quotations are freely bandied about), it is painfully apparent that a cartoon is in progress.

|

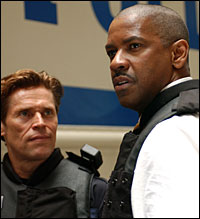

This brings us to Denzel Washington, who plays Detective Frazier, the yin to Owen's yang. Cheerful yet hassled by his insistent girlfriend and a corruption charge ($140,000 worth of drug money gone missing), Frazier could be the cousin of Walter Moseley's Easy Rawlins, the private dick who Washington brought to life in Carl Franklin's Devil in a Blue Dress -- quite wise to the unfairness of this world, and gifted with just enough guile and resourcefulness to land himself in deeper trouble. As the head detective placed on the case, we see the world through his eyes, and what a world it is, crammed with ethnic and racial tensions, recalcitrant cops, unsupportive higher-ups, and pressure-cooker days punctuated by all-too-brief respites at the deli around the corner. The plot dictates that Frazier is essentially a reactive character, forever a half-step behind Owen, but it is amazing to witness Washington (who couldn't be a wallflower if he tried) infuse his role with depth and vigor. He may be chasing his own tail, but he won't let you catch him sweat while he's doing it. Affable and razor-sharp, one moment he might be brokering a truce with the SWAT team, and in the next he might be tormenting a witness (woe be to the interviewee who says his "throat is parched"), or locking laser stares with Foster's Ms. White, or messing with a distraught elderly woman's head ("Did you commit the robbery? ... Naw, I was just playin' with you").

|

|