Ho Lin's official blog site -- home to Ho's commentary, film and book reviews, and meanderings about life.

Thursday, March 30, 2006

Sunday, March 26, 2006

Rock 'n' Roll High School: Asian American Film Festival (Part 3)

Linda, Linda, Linda (2005, Dir. Nobuhiro Yamashita)

When we grow up, we won't quit being kids.

We've only got a little time left to be us.

Nobody does high school quite like the Japanese. While Hollywood films about the Wonder Years are usually bathed in the glow of fond remembrance (see: John Hughes), they're also spiced with a bit of parody (Grosse Point Blank), outright satire (Election), or raunch (American Pie). But in Japan, everything and anything connected to teenagedom is elevated to almost mythic importance -- not surprising, given that it's the last time for many Japanese to express something resembling freedom, individuality, fear, hope. Films running the gamut from the operatic All About Lily Chou-Chou to wistful anime classics like Kimagure Orange Road and box office hits like Love Letter (which hinges on a crucial unrequited high-school romance) have glorified the fumbling interactions, inchoate longings, and life-or-death strivings for acceptance that characterize Japan's 14-to-18 set.

Which makes something like Linda, Linda, Linda even more of a surprise. It hits the same beats the above works do, but in its deadpan amusement, its detached affection, it carves out a new paradigm for the genre: call it pop-punk high school.

|

The set-up couldn't be simpler: It is Festival Week at Shibazaki High School, the annual event in which the school grounds become a carnival, a celebration for outgoing seniors, and a final salute to teenagedom, all in one. A group of girls, including the glowering Kei (Yu Kashii), perky Keiko (Aki Maeda), and the stolid bassist (natch) Nozomi (Shiori Sekine) are throwing together a rock band for the festival's concluding variety show, but a spat between two of them leaves the band without a lead singer, with the show only three days away. Kei makes a wager that the band can draft and successfully train the first person they see to fill the role -- and that person happens to be oddball Korean exchange student Son (Bae Doo-Na), whose command of Japanese is, um, limited.

It's easy to see where this is heading: the band, which sounds endearingly ragged on first rehearsal, will pull together, triumph over adversity, and create a shining moment that the girls (and their brethren) will remember for the rest of their lives. Where Linda, Linda, Linda differentiates itself from the typical genre exercise is in its studious avoidance of the cliches. There are no unenlightened school administrators or bitchy competitors to disturb the course of our heroes, no tensions within the band that threaten to destroy chemistry, not even the blush of a major romantic subplot to satisfy the lovey-dovey audience members. In fact, there is nothing more at stake than throwing together a few songs by the punk rock legends The Blue Hearts, and performing them well. We receive a clue as to where this film will go with the opening narration (see top of this article), which is related in defiant tones by a girl looking straight at the camera -- and then the mood is punctured as a hyperactive student director argues with his DP, and suggests that the girl reads the lines again for his documentary. In one fell swoop, Yamashita is telling us: This high school stuff isn't that serious -- just have fun with it.

|

|

The film is also elevated by Bae, who is probably one of the most fascinating actresses working today (see Take Care of My Cat for a prime example of how she can take over a film without seemingly trying). With her big eyes and gawky figure, she resembles the little sister of Faye Wong (Chungking Express), but in her quizzical spaciness, the way she morphs from puzzled outsider to silly insider, she's like Faye with soul. In her stillness she is mesmerizing; when the infrequent smile bursts out on her face the effect is as liberating as the rainstorm that closes the movie. The last image (and the one that sticks with us) is a close-up on that smile, as the crowds cheer and the glorious power pop of "Linda, Linda, Linda" echoes off the makeshift student stage -- and then the band plays on with the fitting "Endless Song." It won't change world cinema, and it doesn't matter -- Linda, Linda, Linda is a trifle that validates The Blue Hearts, high school, and the necessity of modest pleasures.

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

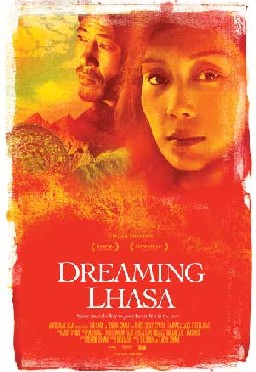

Lhasa Is Missing: Asian American Film Festival (Part 2)

|

Tibet -- the name conjures a multitude of impressions. Spirituality, oppression, resistance, beauty, poverty, epic landscapes, hardy people, sadness, hope. Above all, there's the ongoing Tibet "problem," and its currency among Western spiritual and political circles. When I visited Lhasa in September 2001, mere days after 9/11, it was impossible to ignore the surveillance cameras mounted on the rooftops in the Tibetan quarter of town, or my trip to Drigung Til Monastery, a place which my Lonely Planet guide claimed had a few hundred monks, but which only housed 20 when I arrived -- all the others had fled or had been arrested by the authorities. And then there were the small moments, as when a young Drigung Til monk listened to Radiohead on my minidisc player and asked innocently if he could keep the player, or when the same monk showed the cuts on his head and explained that they were the result of a little brawl with some of the local villagers. Or on a more somber level, witnessing the sky burial of a small boy, his mummified body lying in the monastery courtyard, monks chanting for hours on end before the actual ceremony.

It is easy to forget moments like these when confronted with the more global implications of what Tibet is and what it should be -- and any film that tackles the subject of Tibet is faced with this conundrum. How to fashion a cogent statement about Tibet's life and times, while also presenting the authentic colors of this life? Setting aside the well-intentioned yet glossy efforts of outsider filmmakers (Seven Years in Tibet, Kundun), only one narrative film in recent years has attempted to pull the curtain back: Windhorse (1991), a fascinating study of alienation, subjugation, and cultural confusion in Lhasa that was nevertheless strident in its polemics.

|

The story hinges on a well-worn convention: the delivery of an important item to a missing person. Tibetan by blood but NYC-bred Karma (Tenzin Chokyi Gyatso) is in Dharamsala along with her local pal Jigme (Tenzin Jigme) to film interviews of Tibetan refugees and their stories of resistance and torture. In a few brief strokes, we see that Karma is feisty, confident, and concerned about her grant, her daughter, and her boyfriend in approximately that order. But the standard worldly concerns fall away when she comes across refugee Dhondup (Jampa Kalsang), an ex-monk who now trudges around in the standard flimsy gray suit and red vest that is the civilian uniform of lower-class types across Tibet, and China. Dhondup has a charm box belonging to an acquaintance of his late mother, and his mission is to find the man in India and deliver the box.

Somewhat against her will, Karma is drafted into assisting Dhondup with his search, and as they follow the trail of the missing man, they journey into his past as they happen upon an ex-wife, a belligerent restaurant owner, a hunger protestor, a travel agent, a sweater salesman -- all of them Tibetan, all of them with their own stories, past and present. Following the perfect circle of a prayer wheel, the protagonists' quest takes them on a roundabout journey that ends where it starts, with a final revelation. But Dreaming Lhasa doesn't qualify as a spiritual journey; rather, it is a collection of snapshots, where surprising anecdotes and tidbits of knowledge (i.e., CIA involvement with Tibetan rebellions) bubble to the surface.

|

|

It all comes back to Lhasa: it is talked about in the course of the movie, but rarely mentioned by name. Jigme gets to rock out with a home-grown tune titled "The Dream," but the dreams of these characters are not necessarily about home, or political imperatives. In its tentative but nevertheless engrossing way, Dreaming Lhasa posits a Tibet without the Tibet, where a story or an anecdote proves more substantial than Karma's filmed footage of natives telling her how brutal it was "over there." As she pulls out on a bus at film's end, we ask ourselves, Whither her documentary? Whither Lhasa? and have no answers. Instead, we have tales and shards of memory, a nation reduced to personal meanderings -- a fascinating conundrum in itself.

Monday, March 20, 2006

Hothouse Flower: Asian American Film Festival (Part 1)

San Francisco is a town where you can catch a film festival virtually any day of the week, and as you would expect, these festivals run the gamut, from more-indie-than-indie fringe stuff, all the way to that self-congratulatory gargantuan that is the San Francisco International Film Festival (for a forever-in-progress look at a previous year's fest, see my essay).

Nestling comfortably between these two extremes is the International Asian American Film Festival. Now entering its 24th year, and hopefully past the ups and downs of recent incarnations (last year's offerings were a bit undernourished), this year's festival has a healthy mix of newcomers and showcases -- and far be it for me to deride a festival that can unearth a kung fu classic that contains my name in the title (Dirty Ho).

The phrase "Asian American" naturally brings up a host of interpretations and points for debate. What exactly does "Asian American" mean? How is that particular culture or consciousness defined? What is it allowed to include (films made in Asian Asia, for example)? These aren't questions that will be answered by society any time soon, so the organizers of this event wisely let everyone in on the fun, everything from "pure" Asian cinema to politically and culturally relevant stuff grown here in the US.

I tend to gravitate towards the Asia-bred material at these festivals -- maybe due to my stubborn allegiance to narrative-driven movies. Most of the pioneering work in Asian American film seems to be taking place in non-fiction realms (as it is with American cinema in general), and apart from the rare breakthrough such as Saving Face or Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle (yes, believe it), narrative triumphs seem to be few and far between, at least to these eyes.

It probably doesn't help that most of my cinematic influences (Wong Kar-Wai, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Kurosawa, Taiwan New Wave) hail from the Far East. At their best, their works occupy a certain space in my head, and with their tone and pace, generate fresh ways of looking at environments, relationships, interconnections. Perhaps I'm subconsciously playing into the familiar stereotypes, the exoticism of difference. But if the world hasn't figured it all this out yet, perhaps I can be similarly indulged ...

So with that caveat dully noted, here's my take on the films I'm seeing at this year's festival.

|

"We can't always find what we're looking for, but sometimes, when we stop looking, those things find us."

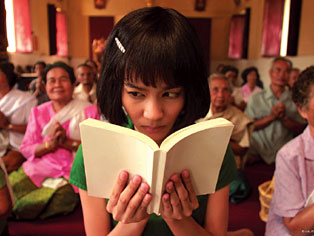

In my admittedly brief exposure to Thai cinema, I've looked for commonalities in storytelling and filmmaking style. I've seen strict crowd-pleasers (Ong Bak) as well as dreamy productions (Last Life in the Universe) and even the works of transplanted directors (the Pang brothers' The Eye). All of these films evince a certain wit, a fluid facility with the camera, touches of the fantastic (Gabriel Garcia-Marquez style), and not a whole lot of staying power. Coming from a region in which nearly all other modes have been exploited (from the epic naturalism of China cinema to the hyperbolic fun of Hong Kong, the genre-mashing exploits of Japan and the emotionally direct dramas of Korea), perhaps Thai films are mapping more genteel territory. Their pleasures are of the elusive kind, like steam in a sauna. You certainly luxuriate in them while you watch them, but how much of it stays with you after it's done?

|

|

|