Wholly Bats: "Batman Begins"

Batman Begins (2005, Dir. Christopher Nolan)

Batman has always been the most saturnine of superheroes -- no ordinary Joe bestowed with extraordinary powers, like the Marvel heroes who have dominated our screens recently, Bruce Wayne and his caped crusader alter ego have never asked for our approval, nor appealed to the common geek in all of us. Rather, he has always been at a remove, remote and lone, rich beyond our wildest dreams, cynical about the infinite fallibility of humankind even as he sets out to reedem it. The impenetrability of his motives, even when draped in Freudian motifs of caves and murdered parents, means that directors can have a field day twisting and distorting him to fit their own artistic and thematic ends. What other superhero could have withstood the charming but dated serials of the 40s, the glorious camp of the 60s TV show, Tim Burton's Gothic carnivals (1989's Batman and Batman Returns), or especially the homo-psychotic bombast of Joel Schumacher, who almost ended the comic book film genre single-handedly with Batman Forever and Batman and Robin?

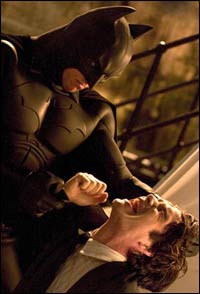

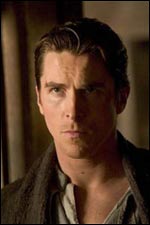

Does it succeed? Mostly. Certainly this Batman has a gravitas that the other big-screen versions lack. Nolan and co-writer David Goyer take pains to ground this Batman in something resembling reality, right down to how the winged one obtains all his wonderful toys (it turns out that Mr. Easy Reader himself, Morgan Freeman, is the Merlin behind the scenes). Most daringly, the movie is focused squarely on Bruce Wayne, his moral and spiritual development, and the back story that leads him to Bat-dom. Thanks to Thomas Newton Howard's brooding, surging score (with an assist by Hans Zimmer), intelligent acting all around, and Nolan's understated approach, the movie holds our interest.

|

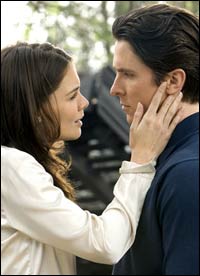

As Wayne's would-be love interest, Katie Holmes isn't necessarily convincing as Gotham's one incorruptible DA, but her appealing girl-next-door quality allows her to skate by, even when the script burdens her with pop-store psychology lines as she attempts to get to the heart of Bruce Wayne ("I heard you were back. But the man I loved, the man who vanished, never came back").

As Wayne's would-be love interest, Katie Holmes isn't necessarily convincing as Gotham's one incorruptible DA, but her appealing girl-next-door quality allows her to skate by, even when the script burdens her with pop-store psychology lines as she attempts to get to the heart of Bruce Wayne ("I heard you were back. But the man I loved, the man who vanished, never came back").It's dialogue like that which tends to keep Batman Begins prosaic when it should be soaring -- I blame most of it on David Goyer, who has never demonstrated much subtlety in his previous writing gigs (Blade, for example). Like FDR, the film's mantra is that there is nothing to fear but fear itself, and just in case we didn't get it, nearly every character soliloquizes about it -- fear's paralyzing consequences, "You always fear what you don't understand," "You must become fear to conquer fear," yaddaya yaddaya. Too bad Nolan doesn't have the visual or emotional dexterity to actually frighten the audience. The film opens with an apocryphal moment, young Bruce Wayne's first traumatic encounter with bats, and it's presented as matter-of-factly as an after-school special, rather than as the subjectively terrifying experience it should have been. Likewise, the brain-bending toxin released by the Scarecrow leads to some nifty visual effects, but nothing that will haunt your nightmares. Batman himself provides some jolting moments as he disposes of various goons, but the zest and wit that informs the brutal moments of other superhero movies -- think of when Doc Oc is first unleashed in the operating room in Spider-Man 2, or even the Joker's demise in Tim Burton's Batman -- is nowhere in evidence here.

Perhaps what Batman Begins should truly have feared is the inevitable air of "been there, done that" that now hangs over every big-budget comic book movie. The film echoes key moments from earlier Batmans, especially the Burton version (a flight by night in which the hero drives the disoriented heroine to the Bat-Cave, or the hissed self-introduction by our protagonist: "I'm Batman"), and as it progresses, Wayne's voyage of self-discovery relents to blurry action scenes and yet another "release poison gas on the city" gambit by the villains, the sense of originality frittered away. One can all but hear the studio suits breathing down Nolan's neck: "But Chris, baby, where's the crazy scheme by the bad guys? Where's the over-the-top car chase? Where's the cheesy one liners?" Nolan handles these scenes in workmanlike fashion, but one wonders what he could have done if the story had remained rooted to Earth -- would Batman's intelligence and detective skills come to the forefront? Would the emotional stakes be raised? Sadly, I'm not sure if he would have risen to that challenge. He's at his best when the characters and stakes remain chilly, as with the folding-back-into-himself, memory-addled protagonist of Memento, or the sleep-deprived cop/criminal in Insomnia. It's just not in him to embrace the hot-blooded, escalating intensity a saga like this requires.

So what we have is a conundrum -- a Batman movie with finely tuned performances and an admirable reluctance to indulge in the garish excesses of previous entries, but lacking in the big beats and outsized emotions that elevate the best comics into the realm of pop art. When Liam Neeson intones, "Now if you'll excuse me, I have a city to destroy," his delivery is subtle, naturalistic, almost normal -- and then you think about the actual lines. If given another chance, Nolan is capable of crafting a sequel that can build on what he's accomplished here -- but as an opening salvo in a reinvented franchise, Batman Begins, like Neeson's performance, is admirable and intriguing without being wholly engaging.

So what we have is a conundrum -- a Batman movie with finely tuned performances and an admirable reluctance to indulge in the garish excesses of previous entries, but lacking in the big beats and outsized emotions that elevate the best comics into the realm of pop art. When Liam Neeson intones, "Now if you'll excuse me, I have a city to destroy," his delivery is subtle, naturalistic, almost normal -- and then you think about the actual lines. If given another chance, Nolan is capable of crafting a sequel that can build on what he's accomplished here -- but as an opening salvo in a reinvented franchise, Batman Begins, like Neeson's performance, is admirable and intriguing without being wholly engaging.

The film centers on Wilhelmina “Wil” Pang (Michelle Krusiec), an overachieving, overworked surgeon who develops a crush on free-spirited ballet dancer Vivian (Lynn Chen). As the two carry on a roller-coaster affair, matters are complicated when Wil's widowed 48-year old mother (Joan Chen) is discovered to be pregnant, and summarily thrown out of her grandparents' home. Outcasts in their own ways, the two share rooms and an uneasy detente in Wil's apartment, both hoarding secrets from the world and each other (the identity of the man who has fathered Ma's kid, Wil's lesbian proclivities). Secondary characters bounce off these two main plots, including frightful would-be suitors with designs on Ma, an African American neighbor who ends up getting hooked on Chinese soap operas, a Greek chorus of hair salon denizens who click their tongues disapprovingly at Mom's antics -- and we haven't even mentioned the fact that the head surgeon at Wil's hospital happens to be Vivian's father ...

The film centers on Wilhelmina “Wil” Pang (Michelle Krusiec), an overachieving, overworked surgeon who develops a crush on free-spirited ballet dancer Vivian (Lynn Chen). As the two carry on a roller-coaster affair, matters are complicated when Wil's widowed 48-year old mother (Joan Chen) is discovered to be pregnant, and summarily thrown out of her grandparents' home. Outcasts in their own ways, the two share rooms and an uneasy detente in Wil's apartment, both hoarding secrets from the world and each other (the identity of the man who has fathered Ma's kid, Wil's lesbian proclivities). Secondary characters bounce off these two main plots, including frightful would-be suitors with designs on Ma, an African American neighbor who ends up getting hooked on Chinese soap operas, a Greek chorus of hair salon denizens who click their tongues disapprovingly at Mom's antics -- and we haven't even mentioned the fact that the head surgeon at Wil's hospital happens to be Vivian's father ... There's a lot to admire about

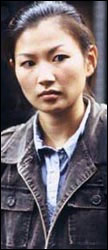

There's a lot to admire about  The wild card in all this is Joan Chen. It's almost -- almost -- possible to believe her as a frumpy housewife who blooms in her newfound freedom, but with her porcelain face and effortless elegance, she seems like she's beamed in from another world. Her presence provides the film with its one element of dissonance and mystery -- while the other characters end up falling into straitjacketed roles as the film progresses (Wil is the uptight careerist who must "let go" and be honest with herself, Vivian is the free-spirited artist who represents desire), Chen only becomes harder to divine. Wu's characters like to over-talk and pontificate, but Chen shrugs it off with silent bouts of TV-watching, and wistful looks that could suggest regret or greater understanding. Her hidden depths remain hidden until the aforementioned

The wild card in all this is Joan Chen. It's almost -- almost -- possible to believe her as a frumpy housewife who blooms in her newfound freedom, but with her porcelain face and effortless elegance, she seems like she's beamed in from another world. Her presence provides the film with its one element of dissonance and mystery -- while the other characters end up falling into straitjacketed roles as the film progresses (Wil is the uptight careerist who must "let go" and be honest with herself, Vivian is the free-spirited artist who represents desire), Chen only becomes harder to divine. Wu's characters like to over-talk and pontificate, but Chen shrugs it off with silent bouts of TV-watching, and wistful looks that could suggest regret or greater understanding. Her hidden depths remain hidden until the aforementioned