We're dated and categorized by everything -- driver's licenses, birth certificates, college dates of graduation, mortgages, kids -- but nothing seems to pigeonhole us, or equate age, quite as much as our affection for the cultural phenomena that we grew up with.

Star Trek fans were beaten into submission with the triple whammy of

Voyager, Star Trek Nemesis, and the aborted

Enterprise series.

Star Wars has run the gamut, transmuting from respected and revered religion (stand up and testify, Reverend Journalist Bill Moyers!) to a sad gathering of desperate freaks and geeks skewered by Triumph the Insult Dog -- and now it has been finally laid to rest, or at least until Lucas pulls another galactic trilogy out of his hard drive while he's getting around to making the small independent movies he's claimed he's wanted to make for the last 30 years. Even something like CBS'

Survivor seems quaint these days, like a familiar, beaten-up toy at the bottom of the pile -- have there really been

eleven of these things since the phenomenon began?

We are inevitably characterized by what we're into, even as our interests wax and wane. My particular pleasure: Bond. James Bond. The second movie I ever saw in a theater was

The Spy Who Loved Me (the first was

Star Wars, natch). It was in Montreal, and I was tired after a day of sightseeing, so my parents had to literally drag me to the cinema. After the movie, we went to a local diner for a late snack, and the entire time we were there, I was humming the James Bond theme -- over and over. In other words, life-changing influence, to the point where I foolishly avoided the Beatles for years, based on a single quip by Sean Connery: "My dear, there are some things that just aren't done -- such as drinking a Dom Perignon '53 above a temperature of 38 degrees Fahrenheit. That's almost as bad as listening to the Beatles without earmuffs."

But say the words "James Bond" on any hip online discussion board today -- try

Ain't It Cool News and

MI6 for starters -- and you'll find a host of young critics (i.e., from a generation younger than myself) slagging last week's selection of Daniel Craig as the latest 007, smugly proclaiming the series dead, dead, dead, far past its sell-by date, prehistoric, a "relic of the Cold War," irrelevant, on the way out, representative of the aged hipsters who have screwed up the world (ouch!), sabotaged by "clueless moron" producers, just plain NOT. Such commentary (or rather, eulogies) has been spirited, but with a whiff of bitterness behind it, as if these critics are spurned lovers, which indicates to me that double-oh-seven still has a hold on us, no matter how much no one would like to admit it. When Craig was introduced as the sixth official James Bond, it made front-page news with most of the major news sites, even while professional and amateur critics made pooh-poohing noises and spent a great deal of time wringing their hands over something they claimed they didn't care about.

I can say all this with impunity because I've been guilty of it myself. Back in 1991, in fact. I wrote a piece for my college newspaper which declared, "Bond is dead, long live Bond." See, it's easy to fall into that sagely pessimistic mode. Of course, back then I had a better case to proclaim Bond finished, as United Artists was virtually insolvent, the public had taken to Timothy Dalton like a snake takes to the mongoose (and this is coming from a man who actually liked good old Timothy), and no plans for anything were forthcoming. Compared to that, the introduction of the hugely unpopular (if you believe the

CNN poll) Daniel Craig seems like a mere hiccup.

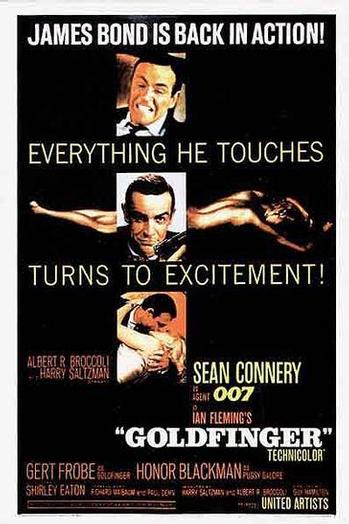

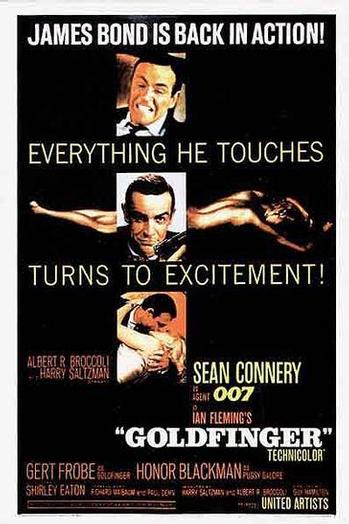

Like most popular phenomena, Bond is more than what he is. As he has been co-opted by the world, he has morphed within the eyes of his beholders, and as with most things that belong to everyone, no one can agree on what actually constitutes Bond. Certainly some aspects are pure bottom line: tall, dark, handsome Englishmen, license to kill, vodka martini, gadgets, lovely ladies, etcetera. But on reviewing the film series, it's remarkable to see how pliable the concept is. For those who enjoy camp or sniggering one-liners galore, look no further than the near-classic blaxploitation of

Live and Let Die, or the not-so-classic "jump on the

Star Wars bandwagon" regurgitations of

Moonraker. Straight spy thriller aficionados can treasure

From Russia with Love. For epic locales, slackening plots, and jaw-dropping set pieces, check out

You Only Live Twice or

The Spy Who Loved Me. For everything wrapped into one neat package, see

Goldfinger. Or for a flawed masterpiece that manages to deconstruct what Bond is about, even as it dutifully fulfills all the formulaic requirements, there's

On Her Majesty's Secret Service.

This pliability is the Bond series' secret weapon. While other genre entertainments calcify within a few entries, 007 continually reinvents himself, acknowledging the end of Cold Wars with a throwaway line, or welcoming disco with an insousciant wink. The gadgets stay blissfully outrageous (everyone groaned at the invisible car in

Die Another Day, but no one will blink when it becomes a reality ten years from now), the exotic locales give way to the latest global hot spots, and even the man himself is redefined with each actor who plays him. But through these myriad transformations, the general structure of things stays the same -- the briefing by cantankerous 'M' (Bernard Lee and Judi Dench may seem worlds apart, but they both share a rough affection for their Bonds), a globe-threatening villain, a hair-raising escape or chase (by land, sea, or air, take your pick), a closing clinch with the heroine. The successful Bond films manage to reflect the current

Zeitgeist without giving in to it, or turning it into cheap homage. Thus, yesterday's glamorous terrorist organization becomes today's media baron megalomaniac, to tomorrow's renegade North Korean general. Like throwing together a jury-rigged vehicle, the Bond filmmakers have become adept at switching out parts on the run and injecting customization when needed. When something works (crazy stunt scene for the pre-title credits), keep it; when it doesn't (shrieking damsels in distress -- hello, Tanya Roberts), throw it out.

We appreciate the familiarity of these Noh-like affairs (thanks to Richard Shickel for the analogy), because we appreciate the formula, and take our pleasures (or disappointments) from how it's toyed with. At their best, the Bond films make you feel pleased with yourself as you glide down the tracks of smooth genre formality -- and then they quicken your heartbeat when they throw in a few roadblocks. The beauty of it is that like the best fast food, one can pick a favorite Bond (movie, actor, whatever) like a favorite sandwich. Perhaps one's preference lies in the elegant yet brutal stylings of director Terence Young (don't fall prey to the common misperception that Bond movies are solely producer-driven -- all of the directors have brought their stamp to bear on the legend, with wildly varying degrees of success). Or if fantastic vistas and clashing armies are your cup of tea, browse Lewis Gilbert's catalogue. Or if sprightly, meticulously shot action scenes are the ticket, check out John Glen. And so on, and so forth.

To be fair, Bond hasn't been culturally

indispensible since the 60s. Back in his heyday, his influence was widespread: these were the event movies of their time (just adjust some of those box office numbers for inflation, and you'll see), and introduced elements that have seeped into every genre film since: soundtracks based on rousing theme songs and stirring melodies (eternal thanks to John Barry), a zippier approach to film editing (courtesy of editor Peter Hunt), and an infatuation with the accoutrements of sophistication, whether that be on the technical side of things (where Tom Clancy,

24, and their high-geek brethern live), or simply living the illicit good life (caper movies, or fleet-footed thrillers with deceit and misdirection as their virtues). Those who say that Bond is no longer relevant have to sit up and pay attention when Peter Jackson notes that the beginning of

The Fellowship of the Ring is based on the pre-title "teaser" structure of a Bond film, or when the urbane Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) gets flirty with his secretary in

Batman Returns -- shades of Moneypenny, there -- before popping down to the lab to snap up the latest gadgets from "Q," er, I mean Lucius Fox (Morgan Freeman). When talents as disparate as Spike Lee, Quentin Tarantino, and Vartan Gregorian all pledge their undying love for 007, it's clear that Bond still exists, even if the series that spawned him isn't aware of it.

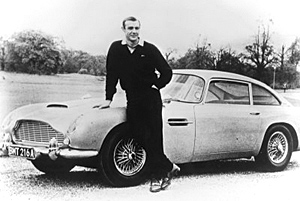

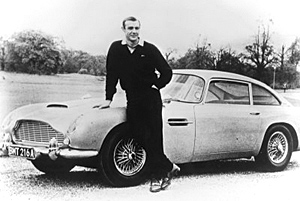

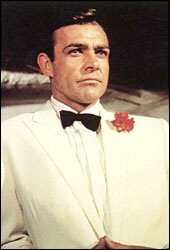

Actually, the Bond series hit its apex with

On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969). As Charles Taylor's excellent

Salon essay notes, the movie ends the story of James Bond with a brave, downbeat flourish. Having pinned themselves in that artistic corner, there was nothing left for the producers to do but retell the same stories, starting with Sean Connery's last hurrah in

Diamonds Are Forever (1971). In general, Connery casts a gigantic shadow over the series, and his performances reflect the unusual contrasts that define it. The son of a truck driver, a rough-and-tumble Scot who has MOTHER tattooed on his forearm, he would be the last person you would expect as a gentleman spy and killer, but in a rare kind of alchemy, the role smoothed out his rough edges, while he gave the part bite and earthiness that established a new kind of action hero. Everyone from Harrison Ford to Bruce Willis has followed in Connery's everyman footsteps, without quite duplicating the sexual magnetism and coiled sense of danger that exemplified him at his peak.

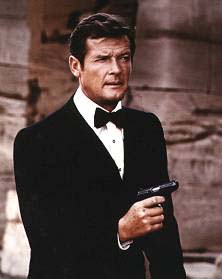

Since Connery's departure, the series has settled into a ragged collection of pretty-good and pretty-bad entries, nothing teeth-grindingly awful (

A View to a Kill notwithstanding), but few moments stick to the memory. Roger Moore was an able successor, bending the part so it fit his own polished, light-as-cream custard image, and it was during his tenure that Bond films became

entertainments, much like amusement park rides -- the thrills were there, but the surprises were diminished. Sensing ennui, the producers made the gutty choice of bringing in Dalton, who appeared in one above-average entry,

The Living Daylights, and then nosedived in

License to Kill. Most Ian Fleming fans will tell you that the earnest Dalton has been the most accurate representation of literary Bond on the big screen to date; this may be true, but the filmmakers cannily recognized early on that the Bond of the novels is a bit of a stiff -- who else would spend whole paragraphs reflecting on the proper way to cook eggs in the morning? In order to make the whole shebang work, Bond needed self-awareness, an ability to chuckle at the flamboyant villains and his pulpy predicaments. And so we have Connery smirk at Dr. No in his very first film: "World domination, same old dream." One thing is for sure -- Fleming would have flung cigarette ash on the bones of

License to Kill with utter distaste. The purists may argue that it brings back the grit and violence of the best Fleming novels, but Fleming would never have gone for something so desultory, so

unglamorous, as dope smugglers in Mexico hiding behind the auspices of Wayne Newton(!) as a television preacher. Without the taste for elegant perversity that Fleming brought to even his toughest tales,

License to Kill blunders into

Miami Vice territory -- only not half as fun.

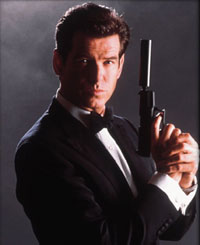

With misfires like that, it's no wonder that most question Bond's relevance in today's world. Yet

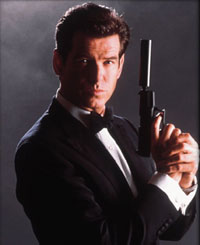

something must still be working (that is, if you're not cynical enough to believe that the box office-busting performances of the past few Bonds are solely attributable to marketing hype). Is that something Pierce Brosnan, who is generally acknowledged as the second best Bond behind Connery? If you compare the Brosnan Bonds to latter-day Moore or even Dalton, they seem positively professional, but their polish fails to conceal a tired, generic air about them. In keeping with that finicky

Zeitgeist, Bond films are now more about the motion than the meat -- throw together some lumbering action sequences set to David Arnold's cut-and-paste techno symphonies, add explosions for good measure, follow the formula, the end. To his credit, Brosnan essayed a more psychologically complex 007 in his films, and his last two entries,

The World Is Not Enough and

Die Another Day, contain some of the most Bondian passages since Connery, although wading through the clamor and clatter of these movies, with their needlessly murky plots and slatherings of special effects, to make it to these moments is like seeking the proverbial oasis in the desert. And although he was superficially perfect for the role, as if minted for it, Brosnan was never entirely comfortable as 007. Tossing puns with the enthusiasm of a wooden soldier, squinting and setting his jaw, sometimes dwarfed by the mayhem around him, he was strangely reticent at times, lacking the avuncular charm of Moore or the all-out charisma of Connery.

So what maintains our interest despite these letdowns? It's an answer as old as storytelling itself -- the pleasure of a tale well told, even if it's been told countless times before. Just as we teeter at the edge of familiarity and unpredictability with everything we encounter in life, we ride that edge with every new Bond film. Will it satisfy our expectations,

and give us something new? As David Arnold has noted, the first ten seconds of a Bond film are always the most anticipatory and exciting, because it is in those ten seconds that we are allowed to think:

This could be the best Bond film ever. And even if the overwhelming majority of the movies fail to deliver on that expectation, they draw us in deep enough to bring us back -- whether it's the impossibly beautiful women who are brainy enough to stand on their own but feminine enough to succumb to Bond's wiles, the kid-on-Christmas-morning glee of his gadgets, or the swinging, uncomplicated masculinity of Bond himself. Or to put it even more simply, it's wish fulfillment at its finest, as producer Albert "Cubby" Broccoli once said:

Men want to be him, and women want to be with him.

Fittingly enough, that leads us to the latest injection of unpredictability into the Bond franchise: Daniel Craig. A relatively unknown actor, brooding in a British Steve McQueen kind of way, he's nowhere near as chiseled or handsome as Brosnan, and marks a startling departure -- he's

blond, for heaven's sake. Already the producers and writers are commenting about the next opus,

Casino Royale, based on Fleming's first Bond novel, and how it will be a "reboot," or

Bond Begins, if you will. More character, more story, less emphasis on endless action, etcetera. We can be forgiven for being skeptical about this -- if the series is starting over, fresh and invigorated, then what is a mediocrity like Martin Campbell (who helmed the lugubrious

Goldeneye) doing anywhere near this project? Why are Neal Purvis and Robert Wade (the culprits behind the uninspired puns and messy plots of the previous two films) scripting this? Perhaps the critics really have it right this time -- with the usual plodding talents behind the camera, coupled with a choice of Bond that seems to have resulted in a resounding "meh" from the media and public,

Casino Royale may turn out to be the moment when Bond finally comes face-to-face with his own irrelevance -- and loses.

More likely, though, is that we will witness another regeneration. Having viewed Craig in

Layer Cake recently, there's no doubt that he's a fine actor.

Layer Cake (or as it's actually spelled,

L4yer Cak3) is no masterpiece, deploying the same Brit gangster formulas we've seen since

Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels, and despite Matthew Vaughn's efficient direction, it never finds its rhythm. But Craig is fascinating, easily flitting between cool-cat calm, fumbling uncertainty, outright panic, and back again. He may not be anyone's idea of Bond, but that might be to his advantage as he reinvents the character.

Casino Royale won't recapture the good old days -- no cultural phenomenon could ever recapture the time and circumstances of its birth -- but if we're lucky, it'll be a bit of much needed resuscitation which will keep this jury-rigged vehicle going for a few more entries, or at least until the next renovation. And having grown up with it, I'm not ashamed to say that this is

my jury-rigged vehicle.

Examined within the context of Lynch's career (especially 2001's Mulholland Dr., which stands as the perfect summation of his work to date), Lost Highway (1997) plays like a free-jazz riff similar to the one morose saxophonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) unleashes early on in the picture -- that is, at once furiously concentrated and all over the place. Anyone with even a glancing knowledge of Lynch's work will see his fingerprints everywhere: a murdered woman; colorfully vulgar psychopaths; deadpan humor that hits home a beat or two later than it ordinarily would; the sense of malign, otherworldly forces at work. Lost Highway doesn't have Mulholland Dr.'s discipline or cumulative power, but when it succeeds, it reminds us why we can always do with a little Lynch-ing.

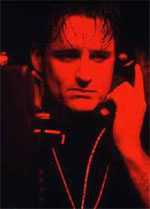

Examined within the context of Lynch's career (especially 2001's Mulholland Dr., which stands as the perfect summation of his work to date), Lost Highway (1997) plays like a free-jazz riff similar to the one morose saxophonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) unleashes early on in the picture -- that is, at once furiously concentrated and all over the place. Anyone with even a glancing knowledge of Lynch's work will see his fingerprints everywhere: a murdered woman; colorfully vulgar psychopaths; deadpan humor that hits home a beat or two later than it ordinarily would; the sense of malign, otherworldly forces at work. Lost Highway doesn't have Mulholland Dr.'s discipline or cumulative power, but when it succeeds, it reminds us why we can always do with a little Lynch-ing. The first 40 minutes of the film may well stand as Lynch's finest cinematic achievement. With both languor and economy, he lays bare the implosion of a psyche, as the videotapes, Fred's feverish visions, and off-kilter uses of mirrors and darkened spaces generate almost unbearable tension. Pullman is often dismissed as a lightweight actor, and many may deride his performance here as glowering and nothing more, but he hits all the right notes (no pun intended) as his sax-man rides the down escalator from bemused to broken. And so Fred ends up in prison for a murder he swears he didn't commit, destined for the electric chair, besieged by headaches -- but within the flash of a hallucinogenic montage, he is literally transformed ... into hunky Pete Dayton (Balthazaar Getty), an unassuming mechanic.

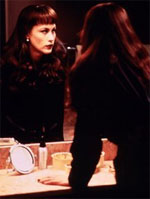

The first 40 minutes of the film may well stand as Lynch's finest cinematic achievement. With both languor and economy, he lays bare the implosion of a psyche, as the videotapes, Fred's feverish visions, and off-kilter uses of mirrors and darkened spaces generate almost unbearable tension. Pullman is often dismissed as a lightweight actor, and many may deride his performance here as glowering and nothing more, but he hits all the right notes (no pun intended) as his sax-man rides the down escalator from bemused to broken. And so Fred ends up in prison for a murder he swears he didn't commit, destined for the electric chair, besieged by headaches -- but within the flash of a hallucinogenic montage, he is literally transformed ... into hunky Pete Dayton (Balthazaar Getty), an unassuming mechanic. It is clear where Lynch is going: Pete is a character invented by Fred's disintegrating mind, a virile rough-houser who is the fulfillment of Fred's wish fantasies, right down to getting the girl (Renee/Alice), but like the titular character of Alice in Wonderland, one must eventually reemerge from the rabbit hole, and thus Fred reappears, and the cycle begins anew. It would have worked if Lynch had invested the second half of the movie with the same craftsmanship and intensity that permeates the first half, but the longer the film runs, the slacker it gets. The actors make do with their sketchy characters, but few distinguish themselves. Getty is surprisingly charisma-free, channeling Charlie Sheen, of all actors. Bravely subjecting herself to the abuse that females in Lynch films must endure (no one else is as consistent at delineating the psychosexual hangups of callow male protagonists as he is), Arquette doffs her clothes and does her best to embody a fetishistic pin-up girl, not least during a strip scene performed at gunpoint. But she does herself no favors with her vacant stares and Bo-Beep voice; contrast that to the performances offered by Isabella Rossellini, Cheryl Lee, and Naomi Watts as other Lynchian ladies in peril. Loggia's Mr. Eddie/Laurent has an amusing vignette with a tailgating driver, but is only a pale echo of Dennis Hopper's landmark loony from Blue Velvet. You know that Lynch's mind is elsewhere when he enlists the help of creepazoids like Trent Reznor and Marilyn Manson on the film's soundtrack -- that's like shoveling parody on top of parody. In the end, only Pullman and Robert Blake, giving his cryptic lines a terrific spin with his patented tough-guy attitude, rise completely above the murk. (Blake's participation in the project is doubly ironic considering Lynch's remark at the top of this essay.)

It is clear where Lynch is going: Pete is a character invented by Fred's disintegrating mind, a virile rough-houser who is the fulfillment of Fred's wish fantasies, right down to getting the girl (Renee/Alice), but like the titular character of Alice in Wonderland, one must eventually reemerge from the rabbit hole, and thus Fred reappears, and the cycle begins anew. It would have worked if Lynch had invested the second half of the movie with the same craftsmanship and intensity that permeates the first half, but the longer the film runs, the slacker it gets. The actors make do with their sketchy characters, but few distinguish themselves. Getty is surprisingly charisma-free, channeling Charlie Sheen, of all actors. Bravely subjecting herself to the abuse that females in Lynch films must endure (no one else is as consistent at delineating the psychosexual hangups of callow male protagonists as he is), Arquette doffs her clothes and does her best to embody a fetishistic pin-up girl, not least during a strip scene performed at gunpoint. But she does herself no favors with her vacant stares and Bo-Beep voice; contrast that to the performances offered by Isabella Rossellini, Cheryl Lee, and Naomi Watts as other Lynchian ladies in peril. Loggia's Mr. Eddie/Laurent has an amusing vignette with a tailgating driver, but is only a pale echo of Dennis Hopper's landmark loony from Blue Velvet. You know that Lynch's mind is elsewhere when he enlists the help of creepazoids like Trent Reznor and Marilyn Manson on the film's soundtrack -- that's like shoveling parody on top of parody. In the end, only Pullman and Robert Blake, giving his cryptic lines a terrific spin with his patented tough-guy attitude, rise completely above the murk. (Blake's participation in the project is doubly ironic considering Lynch's remark at the top of this essay.)

We are inevitably characterized by what we're into, even as our interests wax and wane. My particular pleasure: Bond. James Bond. The second movie I ever saw in a theater was The Spy Who Loved Me (the first was

We are inevitably characterized by what we're into, even as our interests wax and wane. My particular pleasure: Bond. James Bond. The second movie I ever saw in a theater was The Spy Who Loved Me (the first was

We appreciate the familiarity of these Noh-like affairs (thanks to Richard Shickel for the analogy), because we appreciate the formula, and take our pleasures (or disappointments) from how it's toyed with. At their best, the Bond films make you feel pleased with yourself as you glide down the tracks of smooth genre formality -- and then they quicken your heartbeat when they throw in a few roadblocks. The beauty of it is that like the best fast food, one can pick a favorite Bond (movie, actor, whatever) like a favorite sandwich. Perhaps one's preference lies in the elegant yet brutal stylings of director Terence Young (don't fall prey to the common misperception that Bond movies are solely producer-driven -- all of the directors have brought their stamp to bear on the legend, with wildly varying degrees of success). Or if fantastic vistas and clashing armies are your cup of tea, browse Lewis Gilbert's catalogue. Or if sprightly, meticulously shot action scenes are the ticket, check out John Glen. And so on, and so forth.

We appreciate the familiarity of these Noh-like affairs (thanks to Richard Shickel for the analogy), because we appreciate the formula, and take our pleasures (or disappointments) from how it's toyed with. At their best, the Bond films make you feel pleased with yourself as you glide down the tracks of smooth genre formality -- and then they quicken your heartbeat when they throw in a few roadblocks. The beauty of it is that like the best fast food, one can pick a favorite Bond (movie, actor, whatever) like a favorite sandwich. Perhaps one's preference lies in the elegant yet brutal stylings of director Terence Young (don't fall prey to the common misperception that Bond movies are solely producer-driven -- all of the directors have brought their stamp to bear on the legend, with wildly varying degrees of success). Or if fantastic vistas and clashing armies are your cup of tea, browse Lewis Gilbert's catalogue. Or if sprightly, meticulously shot action scenes are the ticket, check out John Glen. And so on, and so forth. Actually, the Bond series hit its apex with

Actually, the Bond series hit its apex with  Since Connery's departure, the series has settled into a ragged collection of pretty-good and pretty-bad entries, nothing teeth-grindingly awful (

Since Connery's departure, the series has settled into a ragged collection of pretty-good and pretty-bad entries, nothing teeth-grindingly awful ( With misfires like that, it's no wonder that most question Bond's relevance in today's world. Yet

With misfires like that, it's no wonder that most question Bond's relevance in today's world. Yet  Fittingly enough, that leads us to the latest injection of unpredictability into the Bond franchise: Daniel Craig. A relatively unknown actor, brooding in a British Steve McQueen kind of way, he's nowhere near as chiseled or handsome as Brosnan, and marks a startling departure -- he's

Fittingly enough, that leads us to the latest injection of unpredictability into the Bond franchise: Daniel Craig. A relatively unknown actor, brooding in a British Steve McQueen kind of way, he's nowhere near as chiseled or handsome as Brosnan, and marks a startling departure -- he's  More likely, though, is that we will witness another regeneration. Having viewed Craig in

More likely, though, is that we will witness another regeneration. Having viewed Craig in