Time Regained: "Three Times Two"

Three Times Two (Original Title: "Tres veces dos"; 2005, Cuba, directed by Pavel Giroud, Lester Hamlet, and Esteban Insausti)

As I mentioned in my review of Suite Habana, which was my favorite film at last year's San Francisco International Film Festival, you can't get much more "foreign" than how Americans tend to present Cuban cinema. In introducing this film, programmer Ivan Giroud even mentioned that Cuba is like "another planet," although he also took care to add that with the new availability of digital video, Cuban cinema is entering its own low-budget indie film period. Fortunately, as an ambassador from another planet, as well as a look at what's new in Cuban cinema circa 2005, Three Times Two, an omnibus of three short films centering around couples, is refreshingly casual.

It's also unmoored from the typical preconceptions about Cuba, all that "land of dance and music and architecture and old cars" stuff, although all three films are unmistakeably preoccupied with history -- history created, lost, reimagined, repossessed. From the romantically sinister stylings of the first entry, "Flash," to the urbanized, strangers-til-we-meet ambience of the last segment, "Luz Roja" (Red Light), the filmmakers are occupied with cinematic predecessors and how they are mapped onto modern-day Cuba, coloring surroundings and stories like watercolors dashed on a canvas. All three movies, shot on digital video before being blown up to 35mm, betray their budgetary limitations and have their awkward student-film moments, but all three teem with imagination, a sense of fun, and the promise of exciting roads ahead.

Pavel Giroud's "Flash" is the most immediately accessible entry of the bunch, centering on a young photographer who becomes obsessed with a "ghost" who mysteriously appears in his photographs of Havana's historic districts. As it turns out, the ghost is the apparition of a Cuban model from 1959, pre-Castro days, and Giroud juxtaposes this rediscovery of pre-Castro Cuban history with a cinematic vocabulary that recalls an earlier age, Hitchcock with a dash of European New Wave, the yearning romanticism of noir strings plus intoxicating jump-cuts and chilly pans. Giroud's actors aren't an especially convincing bunch, and the sudden "stabs" of sound effects so often used in horror films are here in overabundance, but he expertly turns up the screws on the tension, culminating in a finale (and final 360-degree camera movement) that would have done both Hitch and M. Night Shyamalan proud.

Pavel Giroud's "Flash" is the most immediately accessible entry of the bunch, centering on a young photographer who becomes obsessed with a "ghost" who mysteriously appears in his photographs of Havana's historic districts. As it turns out, the ghost is the apparition of a Cuban model from 1959, pre-Castro days, and Giroud juxtaposes this rediscovery of pre-Castro Cuban history with a cinematic vocabulary that recalls an earlier age, Hitchcock with a dash of European New Wave, the yearning romanticism of noir strings plus intoxicating jump-cuts and chilly pans. Giroud's actors aren't an especially convincing bunch, and the sudden "stabs" of sound effects so often used in horror films are here in overabundance, but he expertly turns up the screws on the tension, culminating in a finale (and final 360-degree camera movement) that would have done both Hitch and M. Night Shyamalan proud.

Lester Hamlet's "Lila" is the most ambitious of all three films, an Andrew Lloyd Webber-styled musical set in the town of Zulueta. It is the anniversary of July 26 and the start of the Cuban revolution, and the aged, lonely titular character is caught up in the memories of that time and the young rebel she was romantically involved with. As she reminsces (and sings) about those fateful days, we flit back and forth between a present shot in muted, graying tones, and a doomed romance from the past rendered with a candy-coated, almost festive sheen. Setting aside the potentially dubious project of turning a wrenching episode of Cuban history into West Side Story, Hamlet brings a polished eye to the film. Clever transitions and framing abound, including a standout passage in which we pan across the roof of the old woman's apartment and down to the alley below, where her younger self cavorts with the young rebel, the screen effortlessly saturating itself with color. The music is competently produced and performed, although many of the songs veer too close to adult-pop ballads for comfort -- interestingly, as with many musicals about epochal events, there is a frission between these show tunes that romanticize our young lovers, and the hard facts of history. Ultimately, "Lila" is sabotaged by a third act in which the two lovers are separated in the past by the most mundane of reasons (love triangle, anyone?), but are then reunited in the present day without much rhyme or reason. Nonetheless, this short film's reconfiguration of the Revolution as a lovers' escapade is certainly striking, if not downright subversive.

Esteban Insausti's "Luz Roja" is the most impressionistic

of the three films, and the most polished. It begins as a fractured montage of MTV for the Playboy Channel crowd -- images of naked women standing provocatively in hallways, a man pressed up against a glass door, pleasuring himself. It turns out that this assault of erotica is in the minds of two very solitary people: a psychologist shut away with his blathering patients in an interview room that wouldn't look out of place in a Duran Duran video, and a blind woman who is a peculiarly isolated radio DJ, sitting alone on a stage and awaiting calls from a public that has no interest in dedicating songs. A chance encounter in the rain and a malfunctioning traffic light leads these two lonely souls into a car, where they talk, fantasize scenarios and intimacies, communicate without communicating. This scene, the centerpiece of the film, is as rapturous as any of Wong Kar-Wai's postmodern odes to romance, and Insausti shows off pacing, humor, and sensuality in equal measure. The story concludes on a suspended note, with both would-be lovers making a promise to meet on a corner again someday -- fittingly enough, they separate at the intersection of "Vapor" and "Loneliness" streets, and those two words could stand in as the key attributes of this segment. Divorced from a specific sense of place, its characters prowling skyscraper-slick hallways and anonymous streets, "Luz Roja" gets high on the vapor of style and atmosphere, reimagining Havana as urban hunting ground for the restless and lonely. Insausti's lightning-quick cuts and handheld camera work might be derivative of thousands of other indie filmmakers, but he wrings poetic shots out of his bustle, suggesting there's a sensibility here, as well as some original things on his mind. It will be interesting to see where, his fellow filmmakers in this project, and their brethren go from here.

A common complaint about comic book movies -- that is, the movies actually based on comic books, as opposed to comic-book movies in general -- is that they aren't, well, "comic book" enough. Where is the economy of the storytelling? The relentless momentum contained within those freeze-framed panels? Recent extravaganzas such as Spider-Man and the X-Men films have done a creditable job of translating those thought balloons and zippy scene transitions into a more elegant cinematic vocabulary, but no one has ever attempted a straight-to-celluloid (or hard drive, as the case may be) upload of the complete comic book aesthetic, all moody poses, goofy dialogue, and crash test dummy pacing.

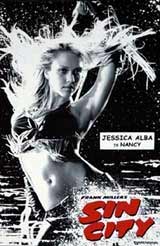

A common complaint about comic book movies -- that is, the movies actually based on comic books, as opposed to comic-book movies in general -- is that they aren't, well, "comic book" enough. Where is the economy of the storytelling? The relentless momentum contained within those freeze-framed panels? Recent extravaganzas such as Spider-Man and the X-Men films have done a creditable job of translating those thought balloons and zippy scene transitions into a more elegant cinematic vocabulary, but no one has ever attempted a straight-to-celluloid (or hard drive, as the case may be) upload of the complete comic book aesthetic, all moody poses, goofy dialogue, and crash test dummy pacing. Ah yes, curves. Virtually every woman in this flick (with the exceptions of Jessica Alba, out of her depth as the stripper with the heart of gold, and Alexis Biedel as a femme fatale of the kiddy sort) gets to show them off. "Sin City" is proud to have its sleazy cake and eat it too, with Old Testament comeuppances, geysers of blood and severed limbs (all served up in classy whites and blacks), cannibalism, castrations, chicks bristling with guns and swords and breasts, several canned hams' worth of noir bon mots, and heads dunked in toilets. For those who claim this is the End of Days when it comes to cinematic morality, it should be added that none of this nonsense can really be taken seriously -- not even on the same semi-serious level as a Quentin Tarantino potboiler such as Kill Bill. Speaking of Tarantino, he directs the film's most memorable passage, a color-coded, hallucinatory conversation between a murderer/private eye (Clive Owen) with a reconstructed face and a dirty cop with a knife sticking out of his head (Benecio Del Toro). It's that kind of movie.

Ah yes, curves. Virtually every woman in this flick (with the exceptions of Jessica Alba, out of her depth as the stripper with the heart of gold, and Alexis Biedel as a femme fatale of the kiddy sort) gets to show them off. "Sin City" is proud to have its sleazy cake and eat it too, with Old Testament comeuppances, geysers of blood and severed limbs (all served up in classy whites and blacks), cannibalism, castrations, chicks bristling with guns and swords and breasts, several canned hams' worth of noir bon mots, and heads dunked in toilets. For those who claim this is the End of Days when it comes to cinematic morality, it should be added that none of this nonsense can really be taken seriously -- not even on the same semi-serious level as a Quentin Tarantino potboiler such as Kill Bill. Speaking of Tarantino, he directs the film's most memorable passage, a color-coded, hallucinatory conversation between a murderer/private eye (Clive Owen) with a reconstructed face and a dirty cop with a knife sticking out of his head (Benecio Del Toro). It's that kind of movie.