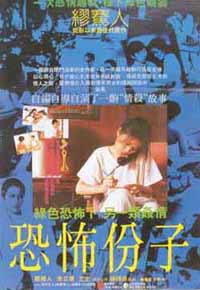

Hopscotch: The Terrorizer (1987, Edward Yang)"Changes are merely rebirths of the past."

- The novelist,

The TerrorizerHou Hsiao-Hsien and Tsai Ming-Liang have had their days in the sun, and yet somehow Edward Yang has been left in the shadows when it comes to appreciating Taiwan New Wave cinema, save the raves of a few critics (for an example, check out

Jonathan Rosenbaum's overview). Browse Netflix and you'll find a healthy sampling of Hou and Tsai's work, but Yang (never the most prolific director – he completed seven feature-length films before his untimely death of cancer last year) is represented by a single film:

Yi Yi, a family drama that is stubbornly art-house in its length (over three hours) and preoccupations (a middle-class Taiwan family comes to grips with its ordinariness).

Not as easily pigeonholed as Hou or Tsai (and certainly not as culturally specific as either of them), Yang is the most cosmopolitan of the Taiwan New Wave directors. Like Hou, he tends to gravitate between two modes: nervy evocations of Taiwan urban life (

Taipei Story,

Mahjong,

Confucian Confusion) and grander-scaled yet intimate family epics (

That Day on the Beach,

A Brighter Summer's Day). What sets him apart from his compadres are French and Italian New Wave elements: plots with pinpoint symmetry, striking tableaus set amidst the easygoing flow of narrative, silences and omissions doing much of the work. While Hou lulls you into Ozu-like reveries and Tsai amps up the quirk, Yang's films are tiny depth charges, dramatic moments sneaking up on us unawares and reverberating long after the fact.

Fortunately, the SF International Asian American Film Festival included three Yang films in this year's program as a tribute to the master: the aforementioned

Yi Yi as well as

The Terrorizer and his masterpiece,

A Brighter Summer's Day (more on that one in a separate review).

The Terrorizer is a fine example of Yang in "urban alienation" mode, but it's more than that. Blending a noir set-up from Antonioni's Blow-Up with a familial crisis that wouldn't be out of place in

Yi Yi, it's a bracing, playful little construction that is nonetheless deadly serious in its intent.

The film begins and ends with a gunshot. It is early morning, a shrieking police car criss-crosses Taipei, arousing the attention of random people. They all have names but are more easily identifiable by what they do: a callow young photographer, a middle-aged doctor (Li Liqun), and his novelist wife (Cora Miao). Trailing the police to a crime scene, the photographer snaps some shots of a dead gangster on the street, before espying his young Eurasian moll leap from a window and land awkwardly on the pavement.

From there we witness the fates of these principals unspool. Eager to provide for his wife, the doctor is angling for a promotion at the hospital where he works by ratting out one of his colleagues (as in all of Yang's movies, the hospital is a locus of inhumanity and incivility). The novelist wife, still mourning the loss of a stillborn child, is tempted to start an affair when an old flame returns to the scene. The photographer, smitten with his snapshots of the Eurasian girl, rents the apartment she escaped and pastes her image on the walls. The Eurasian girl, given to picking up businessmen and stealing their wallets, seeks refuge with her unforgiving mother, who locks down everything valuable in their house even as she continues to pine for the American servicemen who left their lives long ago. All of these characters are defined by some absence in their life, and their individual situations come to a boil when the Eurasian woman makes a random prank call to the novelist, pretending to be her doctor husband's mistress.

|

Like an Altman film or Paul Haggis's

Crash, the film is an intersecting map of coincidences, chance meetings, and tragic consequences. Unlike those movies, however,

The Terrorizer is less interested in histrionics than it is in the physical spaces between us, the private spaces in our heads, and what results when these spaces are yanked away. As the title suggests, each character is engaged in a form of terrorism on the other, yet we rarely see two characters in the same frame, let alone interact with one another. In this cold urban climate, revelation comes in the form of a disembodied phone call, or the faraway glimpse of a woman collapsing in the street, and our sum being is represented by the objects that surround us – the gear the photographer plays with, the white lab coat that grants the doctor husband authority even as it binds him to conformity, the books the novelist must constantly rearrange on her shelves, or the switchblade the Eurasian girl keeps hidden at her ankle.

|

The plot is constructed with precision, and Yang is deft at orchestrating it (if you're in the mood for some thick, juicy literary theory, check out Frederic Jameson's "Remapping Taipei" essay, which parses the urban geography of The Terrorizer to interesting effect). He also has a knack for striking compositions, such as when a pasted-together image of the Eurasian girl flaps in a morning breeze, like an illusion that cannot hold. Some might find the film chilly and distant, an exercise designed for film critics. But to take it that way is shortchanging Yang's dexterity as a director, and the core of emotion at the heart of his films. Take a memorable passage in which the Eurasian's mother, drunk and nostalgic, slips on an LP of the Platters' "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes" and stares at her wayward sleeping daughter with love and accusation in her eyes, followed by a startling cut to the photographer as he watches his jealous girlfriend tearing down his photographs of the Eurasian from the walls, the Platters song soaring to a heartbroken finish and linking them all in complicity. Or the final confrontation between the doctor and his wife, in which a sedate shot of an office conference room is broken up by a flailing of arms and shouts as the husband attempts to drag her away.

|

All the characters in the film have their illusions of love or prosperity shattered, and each receives a comeuppance or redemption of sorts, yet rising above it all is the novelist wife (Miao does nicely understated work). Yang clearly connects the most with her life of quiet desperation, and she is the only one given the opportunity to have an epiphany (in a quiet dinner table scene that foreshadows the down-to-earth frustrations of Yang's family heroes in his later films). The most overt victim of terror, she is also the only one granted a way out, as the novel based on her experiences ironically wins critical notice. As a creator of stories and whole worlds, she is also the fulcrum point for the story's conclusion, a fever climax of murder and revenge contained within a dream, which is possibly within another dream, like

An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge in a city setting. The climax leaves the door open for debate – did what we see just happen? Events would suggest so, and yet the final image is of the novelist wife, now shacked up with her old flame, awakening in a fit of nausea, as if horrified by the events she has imagined, and throwing up, the pregnant artist enduring birth pains. Measured in its progress, an unsettling mix of cool technique and cutting drama,

The Terrorizer is concerned with the spaces we create within ourselves, and suggests that even the most fugitive connections between us are simply figments of our imagination, the novelist in our heads reaching out to fill the void.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home