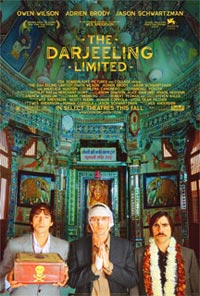

The Long Way Home: "The Darjeeling Limited"

|

Rita: What's wrong with you?

Jack: I honestly don't know. I'll tell you the next time I see you.

Does Wes Anderson have a soul? That seems to be a major preoccupation with critics when it comes to his films. You can spot the technical eccentricities from a mile away: meticulously composed frames, eclectic soundtracks of 60s mod rock and undiscovered modern gems, precision-crafted production design that manages to be fussy and zany all at once. But even though his films are put down for being mannered larks that are too whimsical for their own good, what tends to stick to the memory are faces -- perplexed faces mostly. Taking his cue from silent cinema, Anderson likes to get up close and personal with his characters, lingering over their mute distress, their indecision, their bewilderment. It helps that he also has a stock company of actors (Bill Murray, Owen Wilson, Anjelika Huston, Jason Schwartzman) who know exactly how to achieve major effects with the tiniest of expressions. Many derided Anderson's last film, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, as too pleased with its own frippery, but the wackiness had a point to it: juxtaposed against this funhouse universe, Bill Murray's mournful Steve Zissou gained weight, a soul.

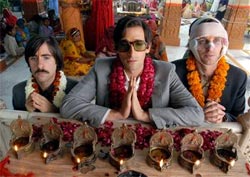

Those who aren't convinced that there's something honest and true going on behind the curtain will most likely not be convinced by The Darjeeling Limited, which nevertheless is both a recapitulation of, and a departure from, the Anderson method. Three brothers -- Francis (Wilson), Peter (Adrien Brody) and Jack (Schwartzman) meet up on the titular train, ostensibly to make a spiritual pilgrimage across India on the anniversary of their father's death. Each of them is nursing his own unspoken hurts and neuroses: Francis, his head swathed in bandages from a vague motorcycle accident, is the den mother, planning each activity out to the minute and insisting that everyone "say yes" to every experience; Peter, hogging all of the dead father's personal belongings, is about to become a father and isn't very happy about it, to the point that he hasn't told his wife he's coming out to India; Jack, still smarting from a recent breakup, is writing bitter autobiographical short stories ("The characters are all fictional," he insists) and wandering around in bare feet like Paul McCartney on Abbey Road.

|

Sounds like a typical Anderson film, right? Wealthy estranged families, deadpan absurdities, culture clash galore. Not exactly -- as if tamed by the very real landscape that the train lumbers through, The Darjeeling Express settles into a lazy rhythm, not so desperate to get to the next visual punch line or bit of whimsy. This sometimes works to the movie's detriment: the first half hour or so is composed of draggy conversations and awkward silences, with nary a hint of comedy or witty character interaction. But even here, Anderson is making a point -- the harder the brothers attempt to buy into the privileged upper-middle-class American vision of spiritual uplift, the harder they fall on their faces. The title itself is indicative; there will be no bullet-train express to fulfillment for these folks, but instead a long, strung-out ride with destination unknown.

|

|

Clocking in at a modest 91 minutes, The Darjeeling Limited tells its story with a minimum of fuss, and gets out while the getting's good. It might not be the best thing Anderson has done -- that honor still goes to Rushmore -- but none of his previous endings have the wry charm this one has, as the three brothers settle in on yet another train. Earlier, on the original Darjeeling Limited, the three have been the typical ugly Americans, bemused at an offer of lime juice, smoking in a non-smoking compartment, antagonizing the steward who came to collect their tickets, immediately heading to the lunch car for cigarettes and a beer. Now they accept the lime juice with deference, respond politely to the steward -- and immediately head to the lunch car for cigarettes and a beer. As we watch the lush Indian landscape outside the train unfold and the credits roll, we're left with the winsome thought that as much as things change us, we are irreducible at heart, and somehow we are okay with it.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home